Cleft Lip and Palate

Published: 29 February 2024

Published: 29 February 2024

When a cleft lip and/or cleft palate is first diagnosed - either by ultrasound scan or at birth - it can be devastating for the parents.

Early support from a specialised interprofessional team can make all the difference in navigating the challenges of feeding, emotional support and, ultimately, surgical repair. So, how do cleft lip and palate present, and how can parents be helped to come to terms with these conditions?

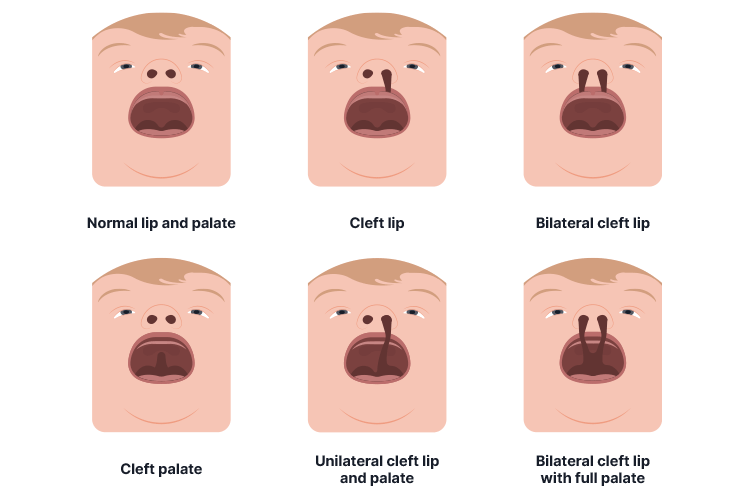

In simple terms, a cleft lip or cleft palate occurs when the lip or the roof of the mouth doesn’t close over properly. This forms a cleft (open space) in the lip or mouth (Raising Children Network 2022). Cleft lips and palates are among the most commonly occurring congenital craniofacial deformities and can occur in isolation or in combination with other congenital abnormalities (Mayo Clinic 2022).

These conditions vary greatly in severity, ranging from a small notch in the upper lip to a large gap in the lip and palate. They can also occur as associated features in over 300 recognised syndromes (Vyas et al. 2020). Although the exact cause of cleft lip and palate remains unknown, it is thought that both genetic and environmental factors may play a part (Better Health Channel 2019).

(RCHM 2017)

As the lip and the palate develop separately and at different times during pregnancy, a baby can be born with either a cleft lip, a cleft palate or both. On average, about 1 in 700 births will be affected by cleft lip and/or cleft palate (Pregnancy Birth and Baby 2022).

It’s also quite common for cleft lip and palate to be associated with other conditions, such as speech difficulties, ear infections and feeding problems (Pregnancy Birth and Baby 2022).

Babies born with a cleft palate often have significant feeding issues as they find it difficult, or even impossible, to suck (Raising Children Network 2022). In most cases, babies born with just a cleft lip can feed well. Breastfeeding is often particularly successful as the breast tissue usually fills the gap caused by the cleft and allows for efficient feeding. However, babies with a cleft palate can’t create enough suction during feeding to draw milk from the breast and expressed milk needs to be given from a specialised bottle with an elongated teat (RCHM 2020).

Mothers should be warned to expect the possibility of milk coming out of the nose along with some sneezing or coughing. In practice, each baby’s feeding needs should be individually assessed as different techniques may suit different babies (CAHS 2021).

(RCHM 2020)

Costa et al. (2019) conducted research into the care of parents of babies with cleft lip and found that although the majority were satisfied with their overall diagnostic experience, many also reported a perceived lack of sensitivity, knowledge and empathy from hospital staff. Some parents also raised concerns about the implications of a delayed diagnosis, including feeding difficulties.

As a result, recommendations were made to help parents access online support via chat lines and social media groups. Enhanced training was also recommended for midwives to address the challenges associated with the postnatal diagnosis and neonatal care of babies with cleft lip and palate.

The face and upper lip develop during the fifth to ninth weeks of pregnancy, so most cleft problems can be detected at the routine 20-week scan or during the newborn examination at birth. The earlier the detection, the better, as this allows time for the parents to come to terms with their baby’s altered appearance and the need for surgery (Vyas et al. 2020).

McElroy et al. (2017) highlight the importance of early detection by performing a thorough examination of both the hard and soft palate as part of the routine newborn examination. This should include visual inspection using a torch and a method of depressing the tongue to allow examination of the whole palate.

The needs of babies with cleft lip and palate can be complex, and often, an interprofessional approach is needed to get the best results (Gatti et al. 2017).

As Vyas et al. (2020) assert, babies with orofacial cleft deformity need to be treated at the right time and at the right age to achieve optimal functional and aesthetic wellbeing. This requires coordinated care drawn from several different specialities, such as oral and maxillofacial surgery, speech and language pathology, and orthodontics. Treatment of cleft lip and palate involves surgery that aims to give the baby facial features that do not attract attention and a physical structure that allows for normal speech and dental development.

The timing and extent of surgery depend on the degree of deformity but usually, the lip can be repaired when the baby is 3 to 6 months old, and the palate at around 9 to 12 months, before the child starts to speak (RCHM 2017).

Although surgery is always necessary, it’s also transformational for these babies, giving them a normal appearance and allowing them to speak and feed without difficulty (Cleft Connect Australia 2016). Follow-up care with specialist teams often continues for several years in order to assess the child’s appearance, speech and hearing in case further follow-up surgery is needed.

Once repaired, a scar - however faint - will remain and could affect the confidence and self-esteem of the child. Some children may also experience speech difficulties requiring ongoing therapy, and some may require further skilled orthodontic and dental treatment for teeth in the area of the cleft.

From the parents’ perspective, there may be difficulties with bonding and a greater risk of postnatal depression for mothers. Disruption to how the parents interact with the child could also contribute to speech and language delay. From the child’s perspective, a cleft lip may also cause difficulties in socialising due to concerns about their facial appearance.

These are all factors that need to be considered by the interprofessional team, and although surgery is an essential first step on the road to healing, it should perhaps be seen as the beginning of the road to recovery and not the end (Kid Sense Child Development 2023).