Every year, congenital cytomegalovirus affects more babies than Down syndrome, toxoplasmosis, and listeriosis (MAMA Academy 2019).

Yet, many people have never heard of this condition, and among those who are infected, most don’t even realize it. If someone contracts the virus while they are pregnant, they can pass it on to their unborn baby with devastating results.

Sadly, many people with CMV miscarry or suffer a stillbirth, and of those babies born alive, about one in five will have problems with hearing loss, cerebral palsy, or physical impairment (MAMA Academy 2019).

Reducing the Risk of Infection

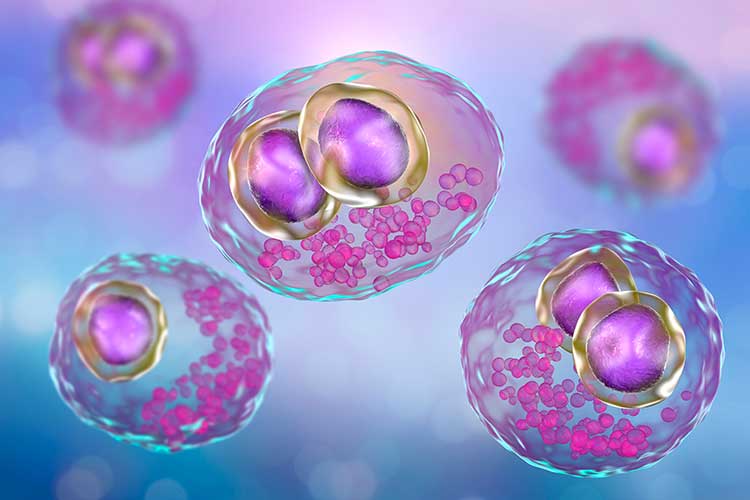

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) belongs to the same group of viruses as the herpes simplex viruses, varicella-zoster virus, and the Epstein-Barr virus. While it’s a common infection that is usually harmless, once it’s in the body, it remains there for life (MAMA Academy 2022).

CMV transmission is known to occur through close contact with someone who already has the virus, the main route of transmission being direct contact with infectious bodily fluids such as urine, saliva, and semen. However, for pregnant people, exposure to the urine and saliva of young children poses a particularly high risk of transmission. This is largely due to the changes to the immune system during pregnancy, which results in depressed T cell function, leaving the body at greater risk of opportunistic viral infections (MAMA Academy 2022).

The incidence of viral illness, the intensity of viral attack, and the severity of illness are all higher in pregnant people than in non-pregnant people. Hormonal factors can also increase the risk (MAMA Academy 2022).

Perhaps one of the greatest challenges presented by CMV is that most infections are asymptomatic. When symptoms are present they often mimic those of other viral infections (e.g. fever, sore throat, swollen glands, aching muscles, and fatigue), meaning the presence of CMV can often go unnoticed (NHS 2023).

Risks to the Fetus

Approximately one in five babies born with congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) will suffer damage, leaving them with life-long conditions such as hearing loss, cerebral palsy, and epilepsy. Despite this, relatively little advice is given about preventative measures to reduce the risk of catching CMV (MAMA Academy 2019).

As a result, CMV Action (2021) has made the following research-based recommendations to help reduce the infection rate and minimize the risk of fetal harm.

1. Risk reduction advice should be routinely given to pregnant people.

Without doubt, the best way to reduce the risk of cCMV is to provide greater antenatal education on the simple hygiene measures that can reduce infection (CMV Action 2021). These include frequent hand washing, avoiding kissing young children on the mouth and avoiding sharing food or drinks with other people (MAMA Academy 2019).

2. Produce and implement clinical guidelines and pathways for testing, improved diagnosis, and management of cCMV.

Greater awareness about the guidelines for managing CMV is needed among midwives and other healthcare professionals so that more families receive monitoring and support (CMV Action 2021).

3. Provide targeted screening for cCMV in children who fail a newborn hearing test to enable affected children to receive treatment much sooner.

Recent studies suggest that targeted newborn screening for babies who fail their initial hearing screening test could be a cost-effective option for identifying and reducing hearing loss caused by cCMV (CMV Action 2021).

4. Provide universal screening for cCMV so that affected children can receive treatment as soon as possible.

Significant advances in diagnostic technology and treatments suggest that universal screening for cCMV could allow affected children to receive treatment much more quickly (CMV Action 2021).

5. Invest in research to support clinical decision-making.

Information on cCMV is limited and often out of date, which makes monitoring treatments and evaluating long-term outcomes unnecessarily difficult. More research-based evidence is needed in order to assess the severity of symptoms and guide clinical decision-making (CMV Action 2021).

6. Develop a vaccine to end CMV.

Developing a vaccine to eradicate CMV is the ultimate long-term goal, although at present it’s thought that the availability of an effective vaccine may be another 10 years away (CMV Action 2021).

Raising Awareness and Preventative Advice

As Cannon et al. (2012) suggest, awareness of CMV still tends to be very low, even though disabilities caused by congenital CMV are more prevalent than many other conditions. This suggests that there is a need for much greater effort to raise public awareness about how maternal infection can be prevented.

As Adler et al. (2004) point out, those who know they are pregnant tend to be highly motivated to follow preventative advice and do what they can to prevent child-to-mother transmission. Sadly, it’s also true that many opportunities for prevention are missed because most people have not heard of CMV or know how to prevent it, and there is often little antenatal education available on the subject.

To date, the only effective means of preventing congenital CMV is through reducing exposure to the virus during pregnancy. Research has shown that rates of maternal infection can be reduced through education regarding sources of infection and improved hygiene (Johnson & Anderson 2014), and there is good evidence to suggest that pregnant people are willing to change their behavior once they are aware of the risks.

It could be argued, however, that avoiding high-risk activities isn’t enough and that there is also an urgent need for more research into possible vaccines and treatments. In addition to this, there is also the need for a much better understanding of the pathogenesis of infection from the parent via the placenta to the fetus.

That said, in recent years, some significant steps forward have been achieved. These include the diagnosis of primary maternal CMV infection in pregnant patients by using the anti-CMV IgG avidity test, and the diagnosis and prognosis of fetal CMV infection by identifying the virus in amniotic fluid (Emery & Lazzarotto 2017).

Whilst the ultimate goal of creating an effective vaccine remains a challenge, the short-term goal of raising understanding and awareness through education remains highly achievable.

As more members of the antenatal care team improve their understanding of the dangers of congenital CMV and then pass that knowledge on to the patients in their care, reducing the devastating effects of congenital CMV may become a realistic possibility.

Topics

References

- Adler, S, Finney, J, Manganello, A & Best, A 2004, 'Prevention of Child-to-mother Transmission of Cytomegalovirus Among Pregnant Women', The Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 145 no. 4, viewed 16 October 2023, https://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(04)00454-8/fulltext

- Cannon, M, Westbrook, K, Levis, D, Schleiss, M, Thackeray, R & Pass, R 2012, 'Awareness of and Behaviors Related to Child-to-mother Transmission of Cytomegalovirus', Preventive Medicine, vol. 54 no. 5, viewed 16 October 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743512000916?via%3Dihub

- CMV Action 2021, Our Recommendations, CMV Action, viewed 16 October 2023, https://cmvaction.org.uk/about-us/our-recommendations/

- Emery, V & Lazzarotto, T 2017, 'Cytomegalovirus in Pregnancy and the Neonate', F1000Research, vol. 6, viewed 16 October 2023, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28299191/

- Johnson, J & Anderson, B 2014, 'Screening, Prevention, and Treatment of Congenital Cytomegalovirus', Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, vol. 41 no. 4, viewed 16 October 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0889854514000631?via%3Dihub

- MAMA Academy 2019, Counting the Cost of CMV Report, Mama Academy, viewed 16 October 2023, https://www.mamaacademy.org.uk/news/counting-the-cost-of-cmv-report/

- MAMA Academy 2022, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Mama Academy, viewed 16 October 2023, https://www.mamaacademy.org.uk/professionals-hub/pregnancy-conditions/cytomegalovirus-cmv/

- National Health Service 2023, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), NHS, viewed 16 October 2023, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cytomegalovirus-cmv/

New

New