Up 40% of hospitalised patients in Australia are affected by malnutrition (ACSQHC 2018).

Without nutritional support, these patients may deteriorate, leading to poor outcomes such as prolonged hospital stays, infection and compromised recovery (DAA 2018).

What is Enteral Feeding?

Enteral feeding is the delivery of liquid nutritional support through a tube inserted into the gastrointestinal tract. It is used for patients who are unable to meet their nutritional requirements through oral intake. This may be because:

- Their oral intake is inadequate (e.g. poor appetite)

- They are physically unable to intake orally in a safe way (e.g. dysphagia, reduced level of consciousness).

(Dietitians Australia 2023)

Enteral feeding may complement oral intake or be used completely in place of oral intake (Dix 2018).

Indications for Enteral Feeding

Enteral feeding is considered for patients who:

- Are unable to meet their nutritional requirements through oral intake, and

- Have a functional and accessible GI tract.

(Adeyinka et al. 2022)

Patients with the following conditions may require enteral feeding:

- Stroke or another neurological condition causing dysphagia

- Serious illness or injury that reduces energy or the ability to eat

- Failure to thrive or inability to eat in young children

- Neuromuscular disorders affecting swallowing, such as Parkinson's disease or multiple sclerosis

- GI dysfunction, disease or obstruction

- Conditions causing increased metabolic and nutritional demands, such as sepsis, cystic fibrosis or burns

- Dementia or other cognitive impairment

- Head and neck cancers

- Reduced appetite due to conditions such as chemotherapy, HIV and sepsis.

(Adeyinka et al. 2022; Dietitians Australia 2023; Complex Nutrition Working Group 2019)

Contraindications for Enteral Feeding

If the patient’s gastrointestinal tract is compromised (e.g. gut failure or intestinal obstruction) or inaccessible via an enteral tube, they may require parenteral nutrition instead. This involves nutrients being inserted directly into the bloodstream via a central venous catheter (Adeyinka et al. 2022; Dietitians Australia 2023).

Older adults or patients receiving palliative or end-of-life care may not be suitable for enteral feeding. You should take into account quality of life, possible complications and expected outcomes when making a decision (DAA 2018).

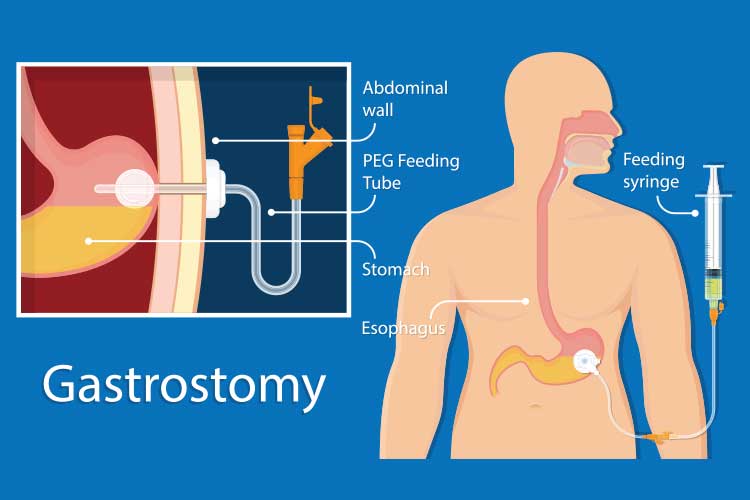

Routes of Enteral Feeding

There are three sites on the body where an enteral feeding tube can be inserted, and several types of tubes that can be used, each taking a different route. This will depend on:

- The intended duration of the nutritional support

- The patient’s condition, and

- Whether there is any trauma or obstruction that would impede access to a certain site.

(DAA 2018)

| Site | Route Options |

| Gastric (stomach) |

|

| Duodenum (small intestine) |

|

| Jejunum (small intestine) |

|

(Adapted from WACHS 2019)

Enteral Tube Positioning

Before the commencement of feeding, you must ensure the tube is positioned correctly. Poor placement or tube migration can cause potentially life-threatening aspiration of feed (DAA 2018).

Placement must be confirmed through x-ray and/or by measuring the pH level of gastric aspirate (refer to your facility’s policies and procedures). A pH of less than 5.5 generally indicates that the tube is correctly positioned in the stomach (WACHS 2019).

Other methods of confirming placement are not recommended as they are less accurate (DAA 2018).

Tube placement should be assessed:

- After the initial insertion

- At least once per shift

- Before administering feed, fluid or medication

- After a break in continuous feeding

- Following oro-pharyngeal suction

- If the patient complains of discomfort or feed reflux

- After the patient vomits, retches or coughs

- If the external tube length has changed

- If respiratory difficuties arise

- Following patient transfer

- When there is any doubt about its positioning.

(WACHS 2019)

Preventing Aspiration

In addition to ensuring the tube is correctly positioned, you can also minimise the risk of aspiration by:

- Elevating the head of the bed by 30 to 45 degrees during feeding and one hour afterwards

- Checking for signs of intolerance (vomiting, abdominal distension, constipation)

- Maintaining good airway management

- Maintaining oral hygiene.

(Souza 2018; CDHB 2022)

Caring for Enteral Tubes

Caring for enteral tubes may include:

- Monitoring and documenting the patient’s weight, fluid balance, biochemistry, blood glucose levels, aspirates and bowel function/stoma output

- Ensuring the tube is positioned correctly

- Introducing food and medications via the enteral tube according to the patient’s care plan

- Assessing the patient’s tolerance to the feeding regimen

- Performing mouth care

- Performing oro-pharyngeal suctioning

- Flushing and aspirating the tube

- Keeping the stoma area clean

- Identifying and reporting any signs of infection, leakage, inflammation or infection around the stoma

- Identifying and addressing symptoms that may require intervention (e.g. reflux, unexpected weight changes, dehydration, allergic reactions, poor chest health).

(WACHS 2019)

Monitoring Enteral Tubes

When caring for a patient with an enteral tube, it is important to regularly monitor the following:

- Food chart (if applicable)

- Nutritional intake

- Fluid balance chart

- Weight/BMI

- Vital signs

- Biochemistry

- Urine output

- Presence of oedema

- Wound staging

- Bowels

- Capillary blood glucose

- Medication

- Nausea and vomiting

- Tube position

- Insertion site

- Tube integrity

- Gastronomy rotation

- Gastronomy progression

- Balloon water volume in balloon-retained tubes

- General patient condition

- Oral health

- The goals of providing nutritional support

- The necessity of providing nutritional support.

(Bapen 2016; WACHS 2019)

Note: Refer to your organisation’s policies and procedures for the required frequency of monitoring.

Complications

Possible complications of enteral feeding include:

- Tube related complications, e.g. migration, blockage, leakage, accidental dislodgement/removal

- Infection, e.g. aspiration pneumonia

- Gastrointestinal complications, e.g. nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, abdominal pain or distension

- Metabolic complications, e.g. refeeding syndrome

- Stoma-related complications, e.g. wound infection, bleeding, leakage.

(Adeyinka et al. 2022)

Conclusion

Enteral feeding is important for providing nutritional support but can be dangerous if performed incorrectly. In order to avoid potentially life-threatening complications, correct and thorough care of the feeding tube is essential.

Note: This article is intended as a refresher and should not replace best-practice care. Always refer to your facility's policy on managing enteral feeding.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

True or false: Enteral tube placement must be confirmed before feeding commences.

Topics

References

References

- Adeyinka, A, Rouster, AS & Valentine, M 2022, ‘Enteric Feedings’, StatPearls, viewed 16 June 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532876/

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care March 2018, Malnutrition, Australian Government, viewed 16 June 2023, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/SAQ7730_HAC_Malnutrition_LongV2.pdf

- Bapen 2016, Enteral Feed Monitoring, Bapen, viewed 16 June 2023, https://www.bapen.org.uk/nutrition-support/enteral-nutrition/enteral-feed-monitoring

- Canterbury District Health Board 2022, Enteral Feeding Policy, CDHB, viewed 16 June 2023, https://edu.cdhb.health.nz/Hospitals-Services/Health-Professionals/CDHB-Policies/Clinical-Manual/Documents/Enteral-Feeding%20Policy.pdf

- Complex Nutrition Working Group 2019, Enteral Feeding in Adults, NHS Highland, viewed 16 June 2023, https://tam.nhsh.scot/therapeutic-guidelines/therapeutic-guidelines/food-fluid-and-nutrition/enteral-feeding-in-adults/

- Dietitians Association of Australia Nutrition Support Interest Group 2018, Enteral Nutrition Manual for Adults in Health Care Facilities, DAA, viewed 16 June 2023, https://www.ncare.net.au/ncarecatalog/resourcecentre/download/file_path/%2Fe%2Fn%2Fenteral_nutrition_manual_june_2018.pdf/ [downoad link]

- Dietitians Australia 2023, Enteral Nutrition, Dietitians Australia, viewed 16 June 2023, https://dietitiansaustralia.org.au/health-advice/enteral-nutrition

- Dix, M 2018, ‘Enteral Feeding: How It Works and When It’s Used’, Healthline, 30 October, viewed 16 June 2023, https://www.healthline.com/health/enteral-feeding

- Souza, J 2018, Nurses’ Guide to Tube Feeding, Shield Health Care, viewed 16 June 2023, http://www.shieldhealthcare.com/community/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/The-Complete-Nurses-Guide-to-Tube-Feeding-Slides.pdf

- Western Australia Country Health Service 2019, Enteral Tubes and Feeding - Adults Clinical Practice Standard, Government of Western Australia, viewed 16 June 2023, https://www.wacountry.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/WACHS/Documents/About-us/Policies/Enteral-Tubes-and-Feeding---Adults-Clinical-Practice-Standard.pdf?thn=0

New

New