Wound Care

A guide to practice for healthcare professionals.

30mUpdated: 17 January 2023

30mUpdated: 17 January 2023

... These are just some of the questions many first-time or novice clinicians may ask when faced with a complex instance of wound care.

The guiding principles of wound care have always been focused around defining the wound, identifying any associated factors that may influence the healing process, then selecting the appropriate wound dressing or treatment device to meet the aim and aid the healing process.

A structured approach is essential, as the most common error in wound care management is rushing in to select the latest and greatest new wound dressings without actually giving thought to wound aetiology, tissue type and immediate aim.

If best patient outcomes are to be achieved, applying evidence-based wound management knowledge and skills is essential.

This wound and dressings guide will identify some of the most common wound types and guide you in setting your aim of care and selecting the best dressing or product to achieve that aim.

Holistic Assessment (HEIDIE)

The first thing to do before addressing any wound is to perform an overall assessment of the patient. An acronym used to guide this process step by step is HEIDIE:

- History - The patient's medical, surgical, pharmacological and social history.

- Examination - Of the patient as a whole, then focus on the wound.

- Investigations - What blood tests, x-rays, scans do you require to help make your...

- Diagnosis - Aetiology / pathology.

- Implementation - Implementation of the plan of care.

- Evaluation - Monitor, assess progress and adjust management regimen, refer on or seek advice.

So, with this in mind, and having completed a thorough overall assessment, a wound assessment can now be conducted.

The five parameters to consider in wound assessment include:

Tissue type

Necrotic, infective, granulation, hypergranulation, poor-quality granulation, epithelium and macerated

Wound exudate

(Type, volume and consistency)

Periwound condition

(This is the area that extends 4 cm from the edge of the wound, although we are now being asked to consider the skin up to 20 cm from the wound edge where possible)

Pain level

(At dressing changes, intermittently or consistently)

Size

(length, width and depth)

How to Measure Wound Dimensions

Download

InfographicDescriptors used to identify the tissue found in wounds are:

- Necrotic eschar

- Necrotic slough

- Infective

- Granulation

- Hypergranulation

- Poor-quality granulation

- Epithelium

- Macerated

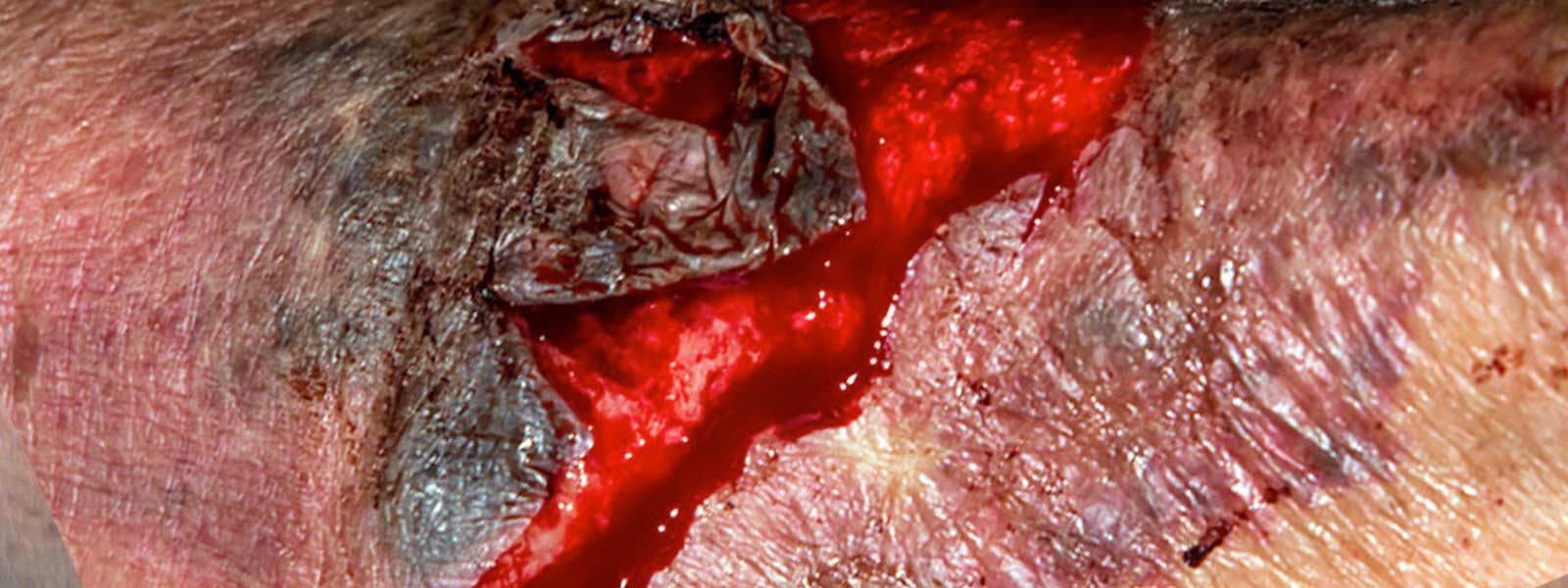

Necrotic Tissue

Ideally, the quickest (and often safest) way to remove necrotic tissue is to involve a surgeon who will then surgically debride the offending tissue.

If this is not possible, then a skilled clinician may be able to conservatively sharp-debride the tissue to just above the viable base.

If this is not possible, then dressings known to aid autolytic debridement should be selected and used according to manufacturer's instructions. An important aspect to consider is that when debriding wounds autolytically the wound may appear deeper as the necrotic debris is removed, revealing the true depth of the wound.

Important: Without a doubt, removal of necrotic tissue and management of infective tissue are two priorities in wound care.

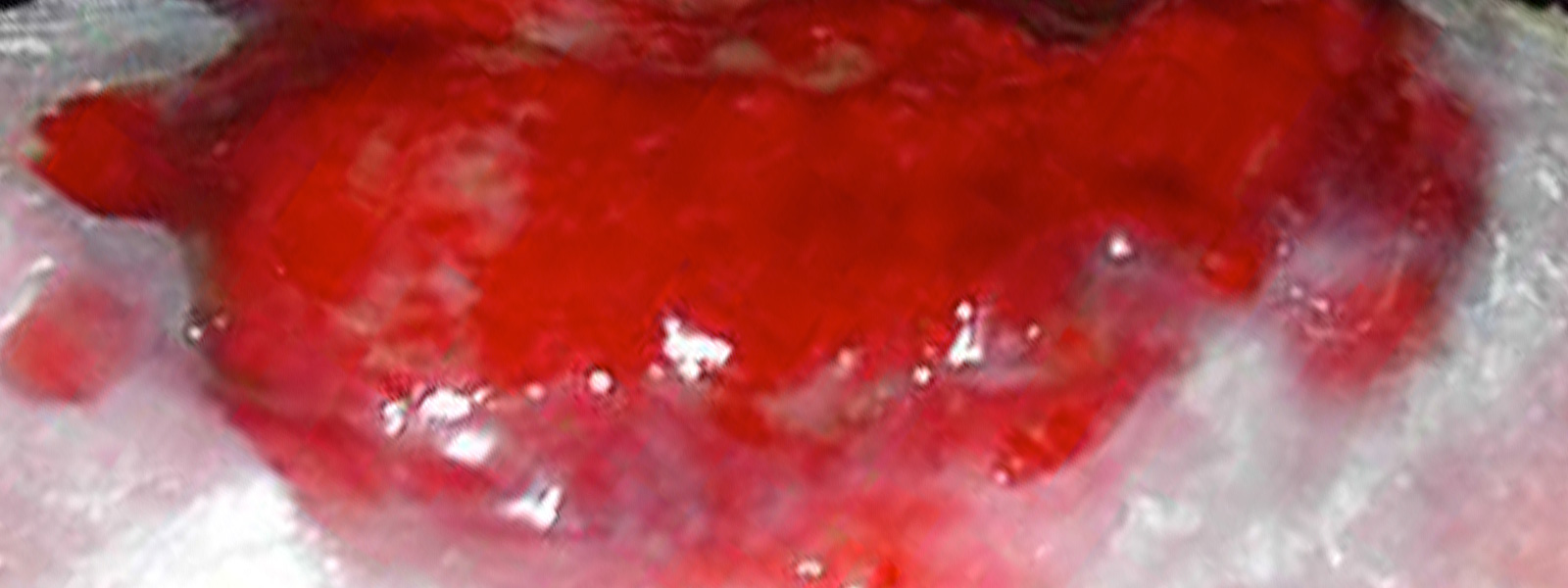

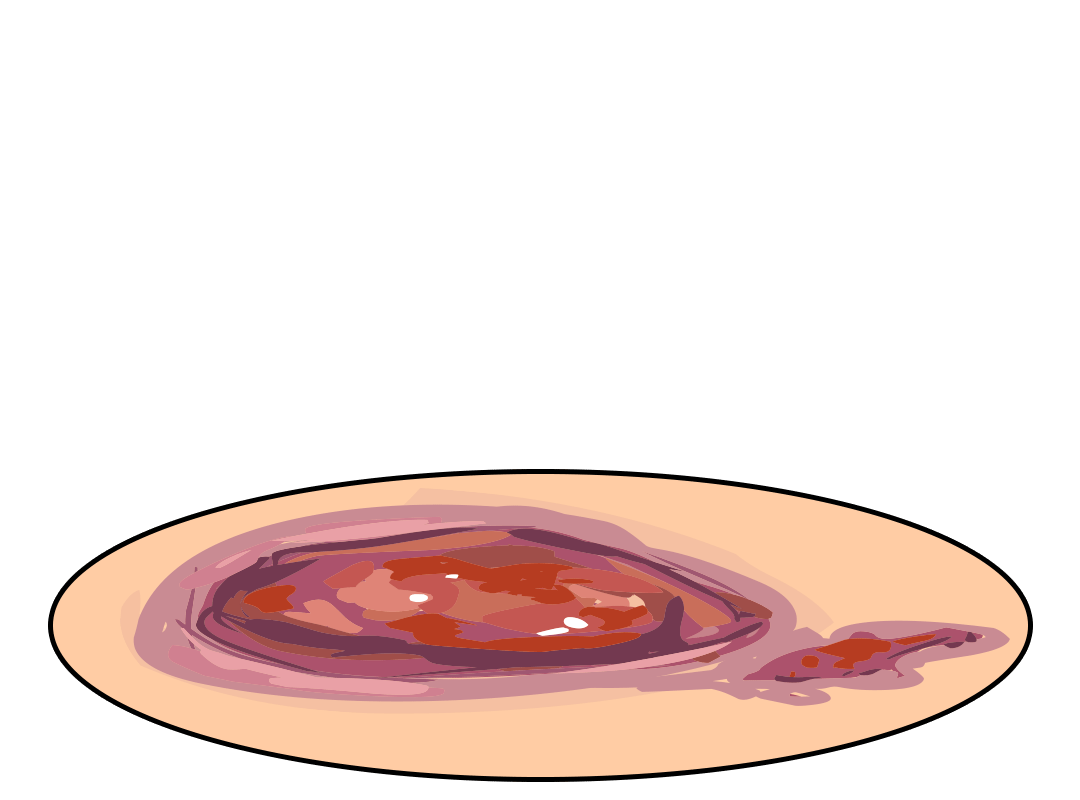

Granulation Tissue

Granulation tissue (firm, beefy red tissue) requires some exudate management and protection.

A dressing that maintains a minimally moist environment and protects the tissue, is generally required.

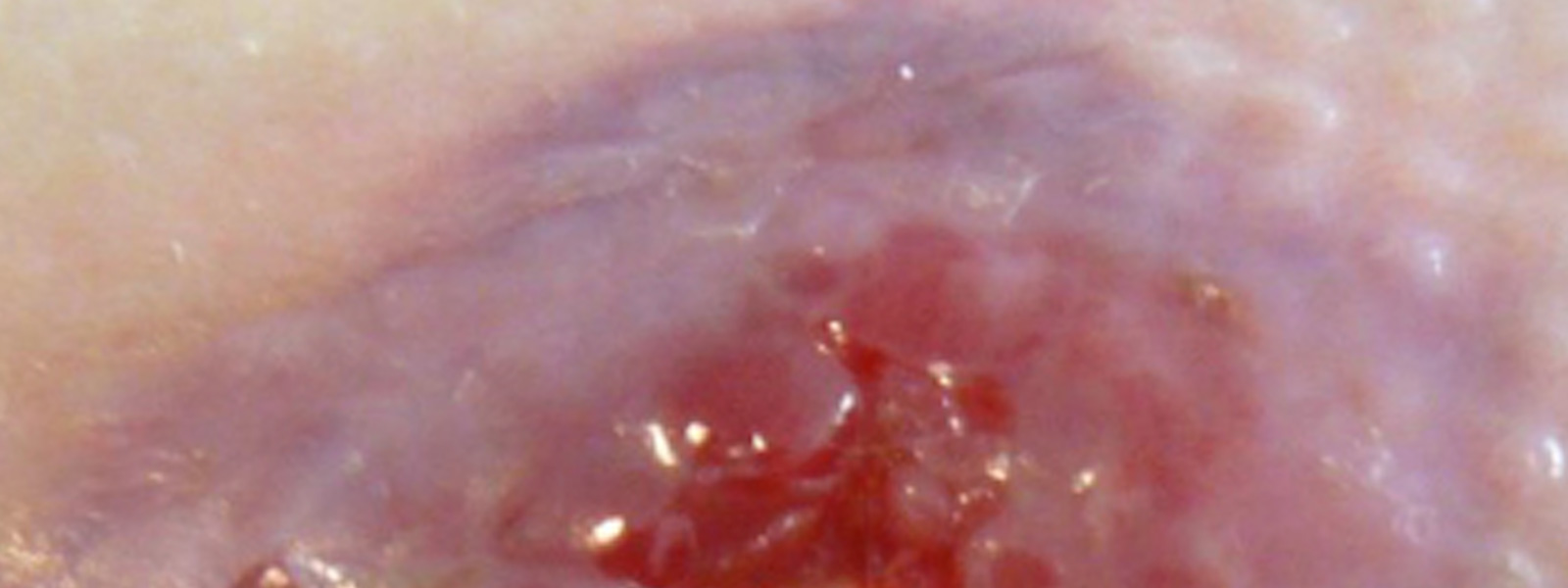

Hypergranulation

This soft, gelatinous, highly exuding tissue requires specific treatment. Some clinicians believe the use of silver nitrate (burning the tissue back) is the best option.

It has been my experience that an approach to bacterial load, direct pressure and dressings that will manage moisture are more acceptable. Newer research is also indicating that hypergranulation is more than likely associated with biofilm and hence, microbial load (Swanson et al. 2022).

Infective Tissue

Infective tissue is best removed when possible by employing the same methods as with necrotic tissue. Antibiotics need to be prescribed when the wound is causing spreading and systemic infection. Exercise caution when debriding infected necrotic tissue as bleeding may occur; generally a few days of antibiotic therapy prior to debriding is ideal when performing in a community setting.

If the wound is locally infected, the clinician may choose to manage the infective tissue with debridement and topical antimicrobials (not topical antibiotics) (Lipsky & Hoey 2009). Topical antibiotics may be used in specific circumstances - for more information, refer to Wound Infection in Clinical Practice: Principles of Best Practice .

Another consideration if colonisation is of concern, is to use generalised body skin-antiseptic cleansers to reduce the possibility of bacteria colonising from one area to another.

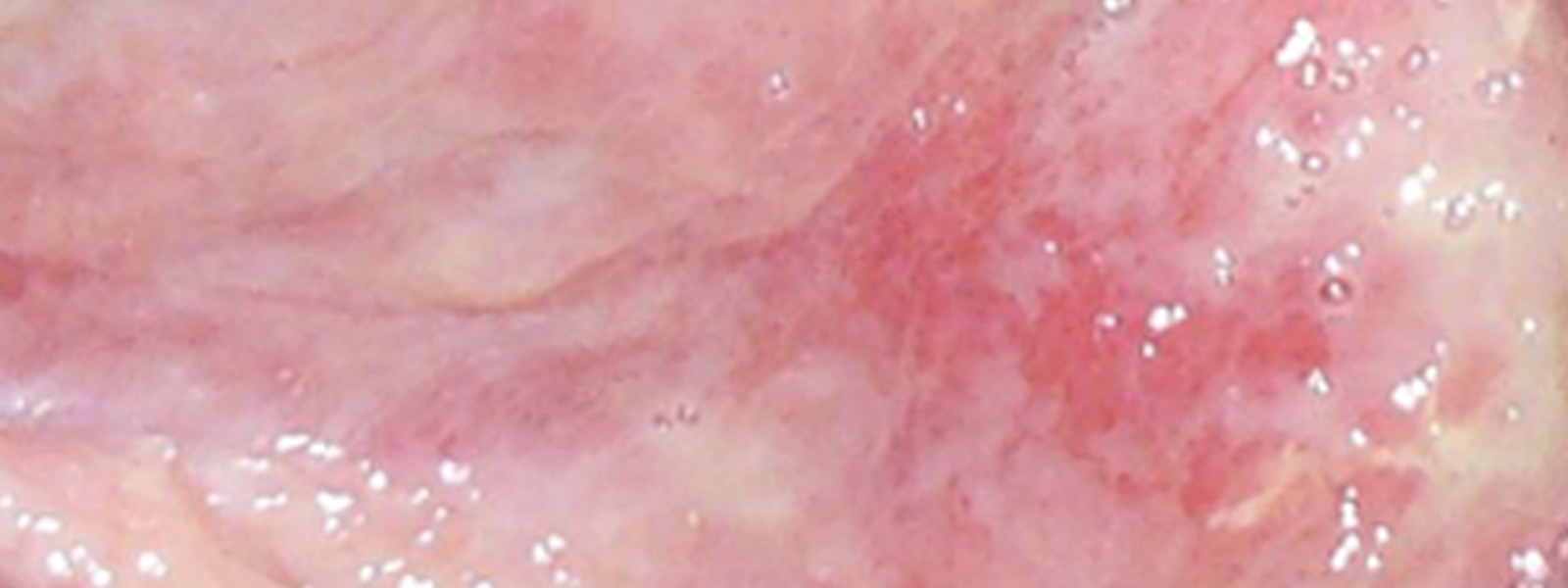

Epithelium

The pale, pink/mauve tissue usually found at the edges of wounds, healing by secondary intention, requires protection. If the wound is superficial/partial thickness then islands of epithelium may also be found sprouting up from skin appendages.

This tissue responds poorly to too much moisture and in most cases a dressing that protects this tissue from the effects of moisture is used. The use of barrier agents ensures this. The area is also particularly susceptible to friction and shear, which must be eliminated.

Poor Quality Granulation (Agranular)

The term used to describe pale, grey/brown/red granulation tissue.

The general approach is to use an antimicrobial and exudate-management dressing, reviewing blood profiles and concentrating on nutrition to help grow stronger better-quality tissue.

Maceration

The term used to describe pale, grey/white tissue found at the edges of a wound. Some clinicians believe maceration is overhydrated keratin and not to be worried about, however, take note that when appearing on weight-bearing areas of the body the soft, soggy edges of a wound will collapse under pressure and will become larger.

With the above information, it is now time to undertake wound care specific to the type of wound.

Dressing Surgical Wounds

Most surgery can be categorised into two groups: elective ('clean') and emergency (this is often referred to as 'dirty').

A surgical wound of the latter category has a higher incidence of dehiscence or complications.

Dehiscence is defined as:

'Separation of the layers of a surgical wound, it may be partial or only superficial, or complete with separation of all layers and total disruption.'

(Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health 2003)

There are a number of well-identified risk factors that can lead to wound dehiscence, including being overweight, increasing/advanced age, poor nutrition, diabetes, smoking and having had radiation therapy previously in the area.

The elective case has the opportunity to correct some of these risk factors; however, the emergency case may not have such an opportunity.

Suture Line

The simple, straightforward suture line is generally treated with a dressing that will manage a small amount of anticipated, early inflammatory exudate and provide a waterproof covering.

All surgical wounds do require support and this is an important factor both for reducing oedema and ensuring patient comfort.

This type of dressing is generally left intact for five to seven days and then removed for inspection of the suture line, with the view to remove the staples or sutures as prescribed.

Suggested dressings to achieve the aims for simple suture lines include: Opsite™ Post-Op and Mepore Pro™.

Type: Composite dressing.

Features: Absorbent, self-adhesive, cushioned, breathable, waterproof.

Uses: Surgical wounds, cuts, abrasions, low to moderately exuding wounds.

Examples: Opsite™ Post-Op, Mepore Pro™.

Care of this simple suture line then involves continued support and hydration. For this, some surgeons prefer supportive adhesive flexible tape for ongoing scar hydration, such as Fixomull™ and Mefix™.

Type: Adhesive flexible tape.

Features: cut to size, adhesive, flexible, allows hydration.

Uses: fixing primary dressings, catheters and tubes.

Examples: Fixomull™, Mefix™.

Dehisced Surgical Wound

The dehisced surgical wound requires a thorough assessment of cavities or structures involved, as well as checking for the presence of foreign bodies, infection and/or necrotic tissue. Once these parameters have been considered, an aim can be set.

Removal of necrotic tissue and management of infection is paramount to move on to the wound healing phase.

Surgical debridement may leave large cavities or areas of raw tissue, which can ideally be managed with a topical negative pressure device. This wound care ‘vacuum cleaner’ will remove excess exudate and contain it in a canister, away from the wound surface.

Due to the negative pressure, the wound edges are drawn in, helping to promptly reduce wound surface. This also reduces oedema, an important aspect to consider in all instances of wound care.

Dressing Abrasions

These wounds are generally acute and, in most circumstances, go on to heal almost regardless of what is done. Simple abrasions, in particular, if not managed by a healthcare professional, form a scab that eventually drops off, revealing a healed area beneath.

The issue here however, is that this type of healing is slow and can result in an unacceptable scar.

The best management of an abrasion is to stop the bleeding, give the area a good clean with an antiseptic and then apply a mesh dressing that will protect the superficial raw area and allow new tissue to form quickly without being damaged when the first dressing is attended. Mesh dressings for this purpose include: Mepitel™, Urgotul™, or Hydrotul™.

Type: Mesh contact layer.

Features: low-adherence, supportive, allows exudate to pass through, transparent.

Uses: abrasions, skin tears, lacerations, ulcers.

Examples: Mepitel™, Urgotul™, Hydrotul™.

The secondary dressing on this mesh is generally a light absorbent adhesive pad, such as Cutiplast Steril™ or Primapore™.

A secondary waterproof dressing is generally not recommended for this first dressing due to the risk of infection – the excessive heat and moisture will create an environment conducive to bacterial growth.

At the next dressing change, if there are no signs of infection, then a waterproof dressing can be used as the secondary dressing, provided all environmental considerations have been made.

Type: Super-absorbent.

Features: super-adsorbent, self-adhesive, cushioned, breathable.

Uses: surgical, cuts, abrasions, lacerations.

Examples: Cutiplast Steril™, Melolin™, Primapore™.

Dressing Lacerations

Simple Lacerations

After a thorough assessment, a small, simple laceration is generally managed with antiseptic cleansing, Steri-Strips™ and either a waterproof, light, absorbent dressing or a non-waterproof, light, absorbent, adhesive dressing, using the principles mentioned earlier about the risk of infection.

Type: Wound closure.

Features: Supportive, breathable, self-adhesive, non-invasive.

Uses: Surgical wounds, lacerations.

Examples: Steri-Strips™, Leukosan Strips™.

Complex Lacerations

More complex lacerations may be referred to an acute care facility or surgeon after initial assessment.

Foreign bodies and penetrating, deep lacerations may involve tendons and nerves, which will require specific specialised care.

The post-surgical wound will then need to be well managed to avoid infection. An antimicrobial dressing that is also absorbent and protective would be ideal.

Dressing examples include: Aquacel Ag™ and Aquacel Foam™ non adhesive, Acticoat Flex™ and Mesorb™, Atrauman Ag™, and Zetuvit™.

The dressings should be fixed in place with a firm crepe bandage and appropriately-sized tubular compression bandage (e.g. Tubigrip™) if the wound is on a limb.

Type: Antimicrobial dressing.

Features: reduces the risk of infection, kills bacteria.

Uses: pressure ulcers, venous ulcers, surgical sites.

Examples: Aquacel Ag™, Aquacel Foam™, Acticoat Flex™, Mesorb™, Atrauman Ag™, Zetuvit™.

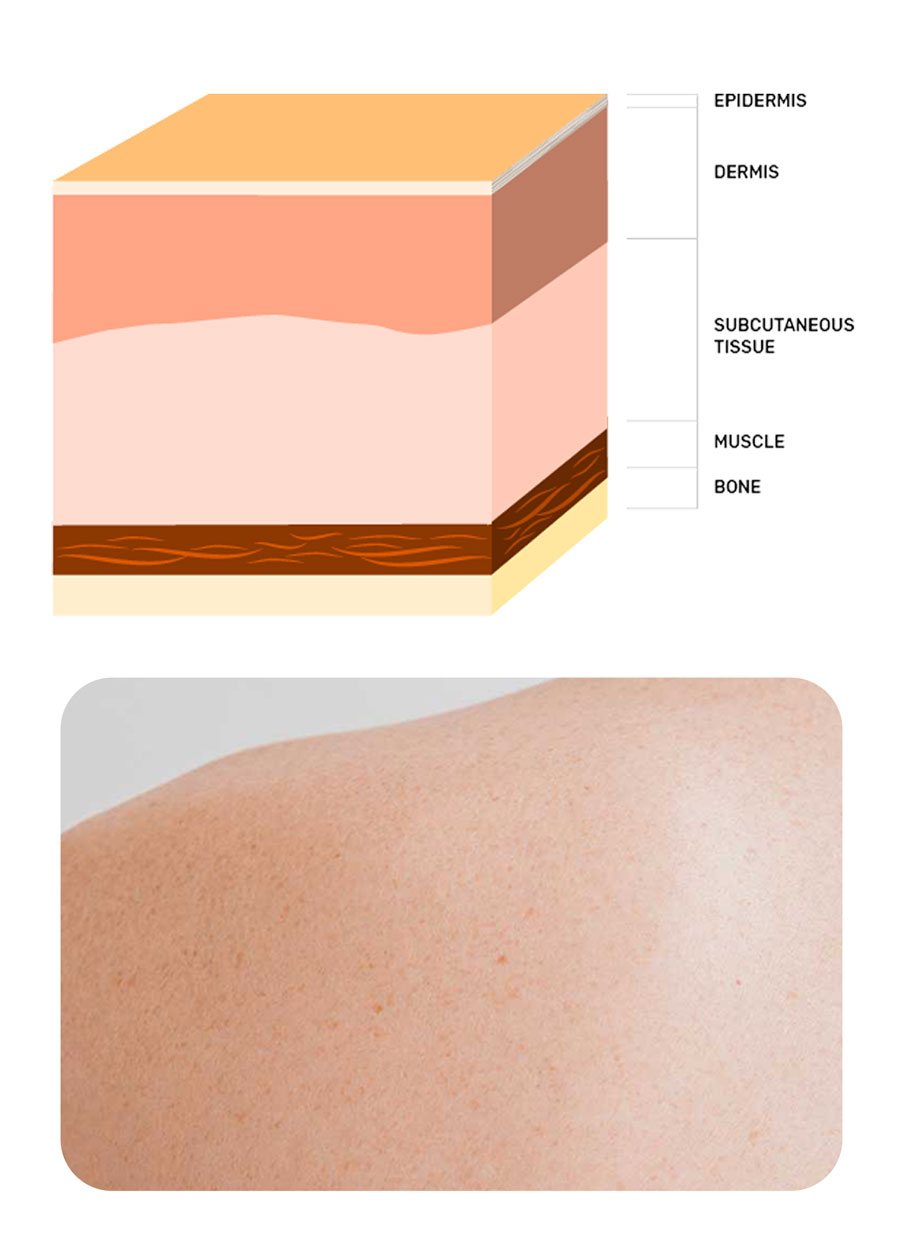

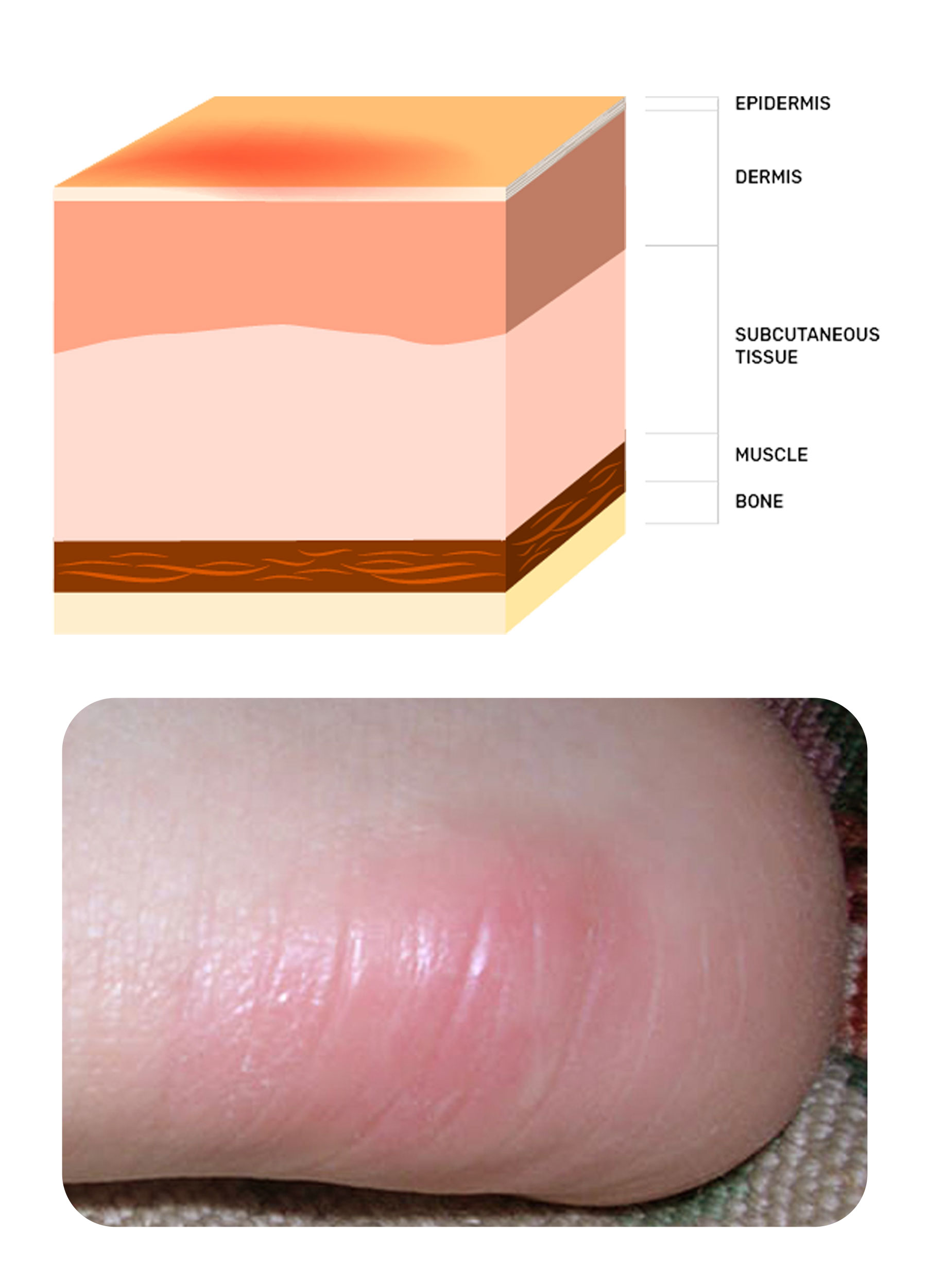

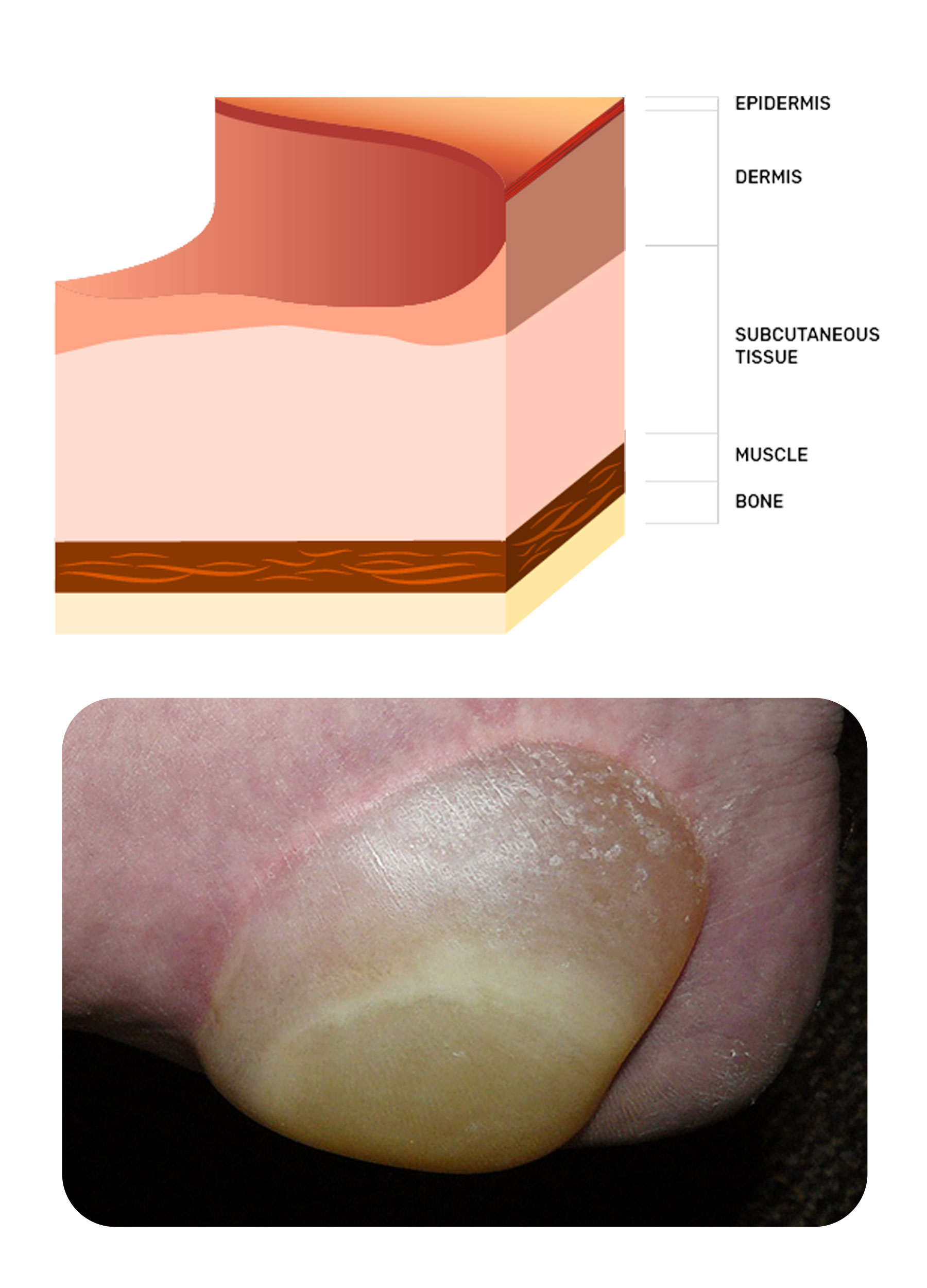

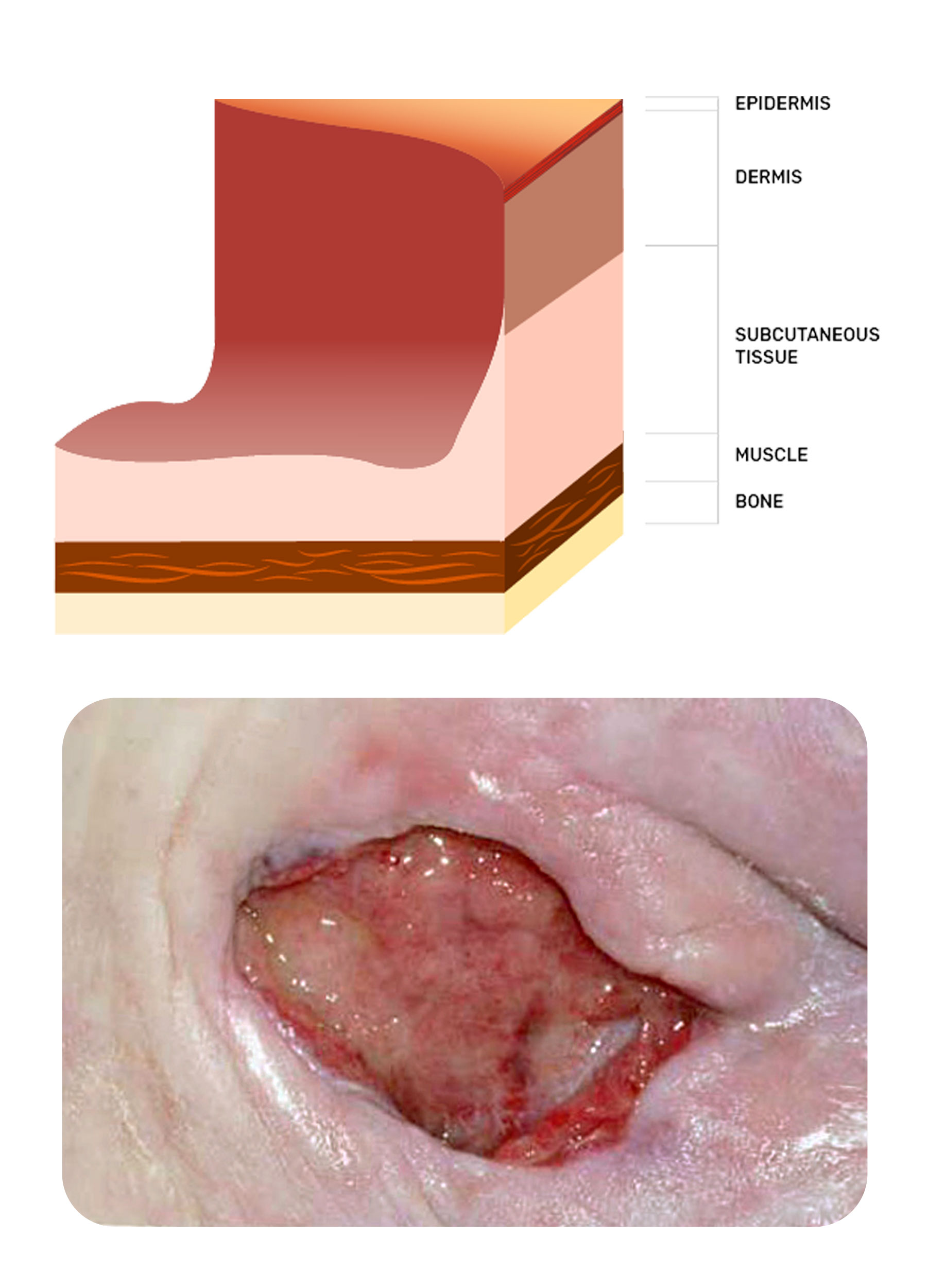

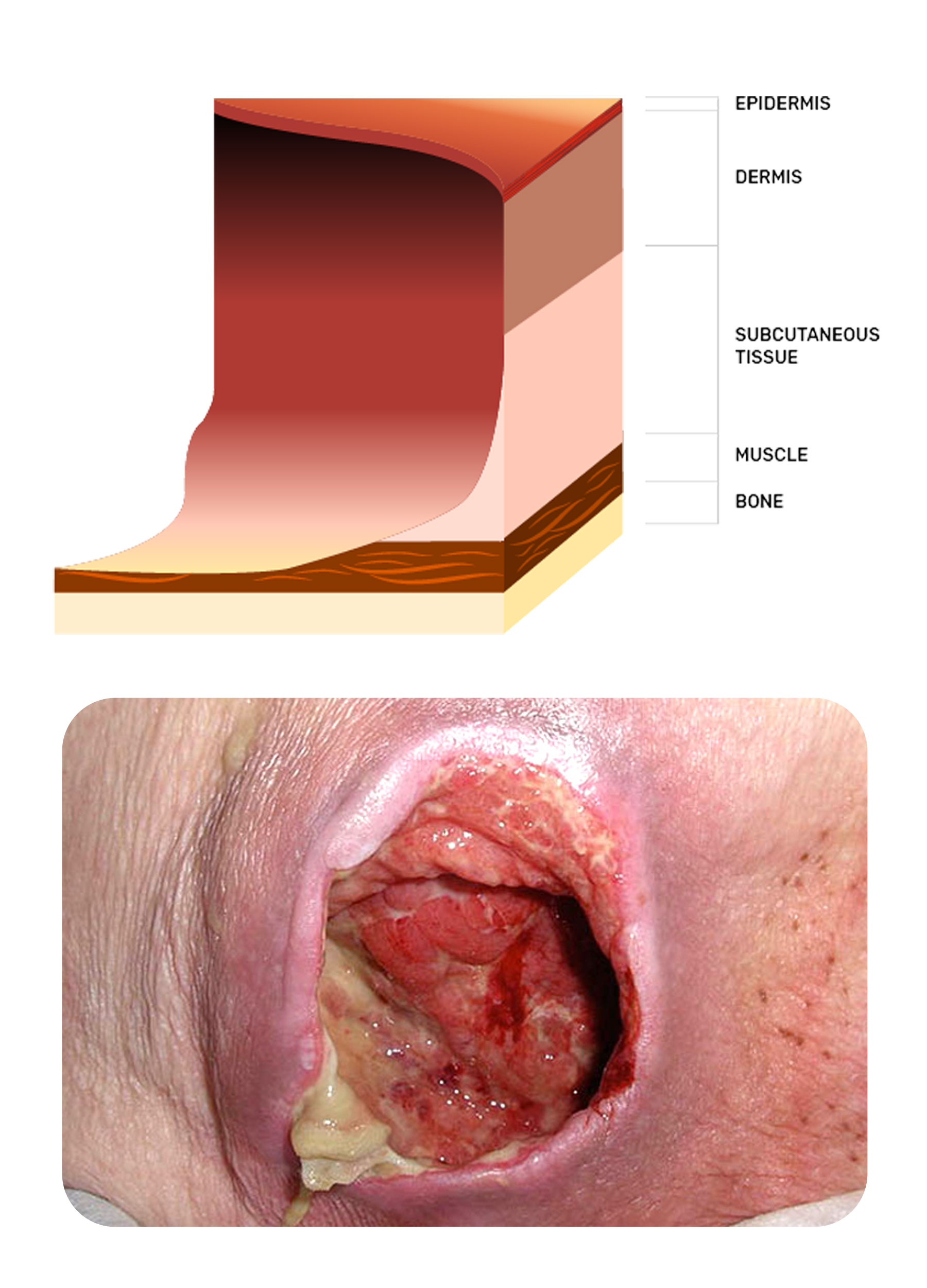

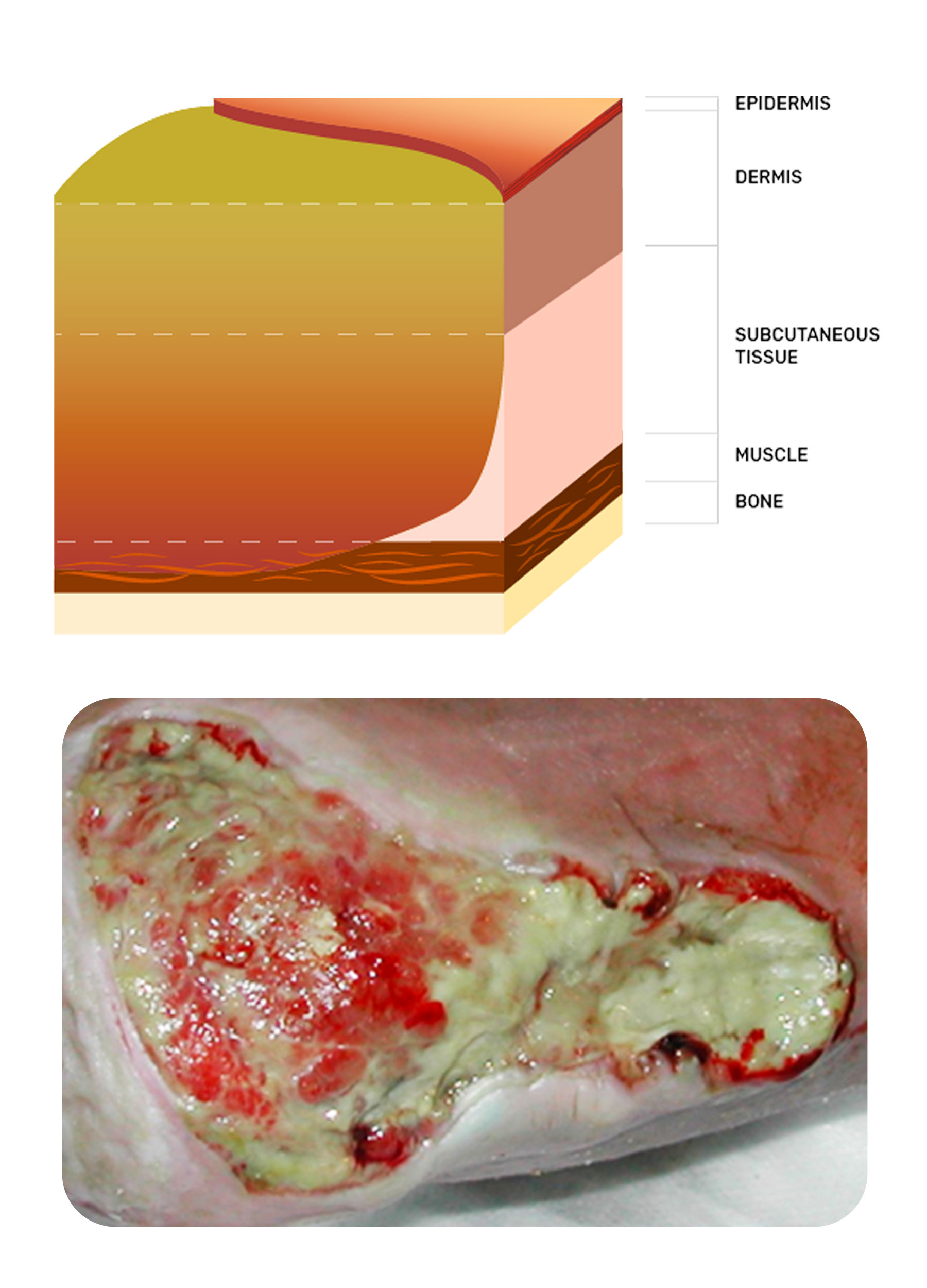

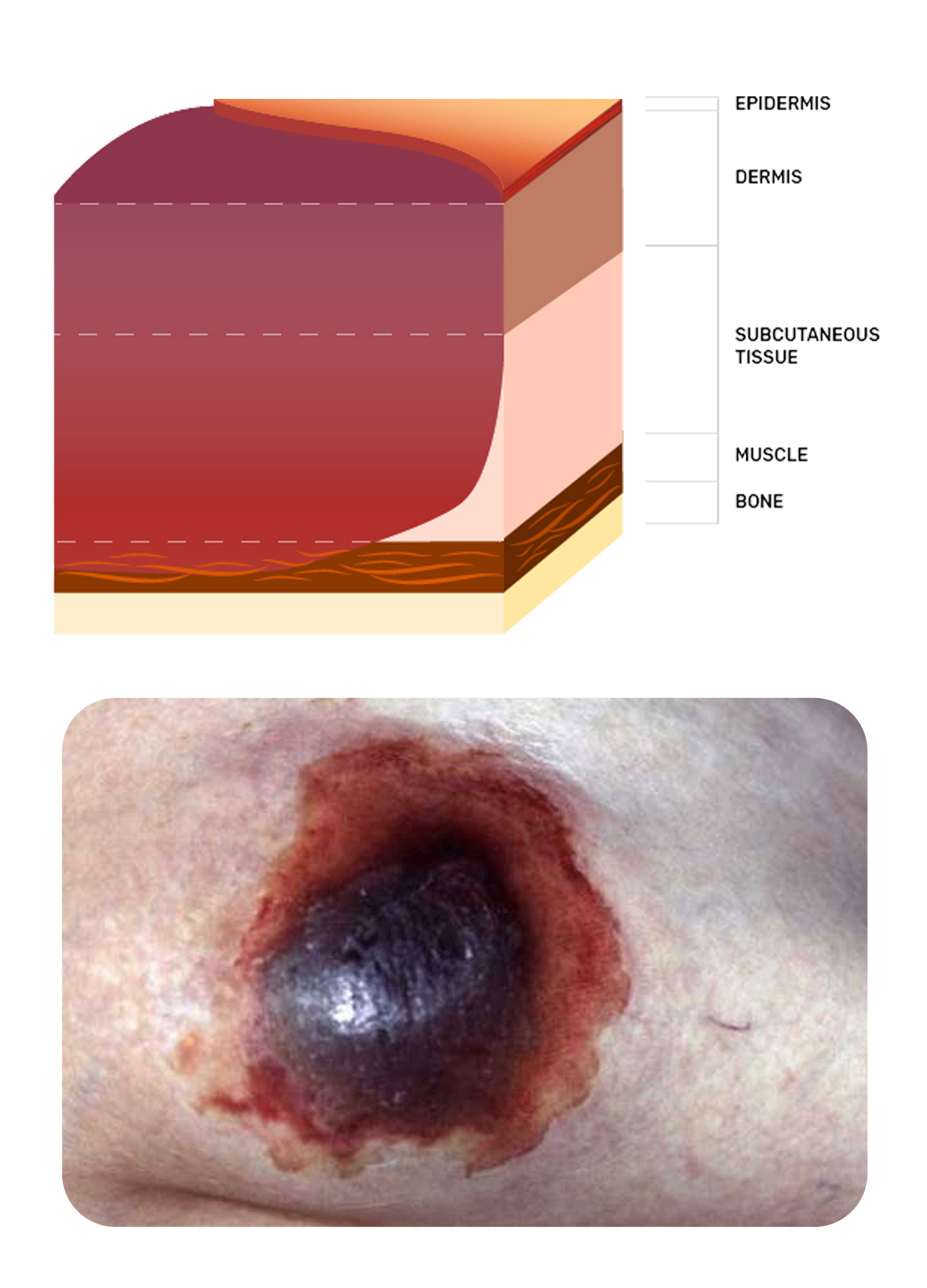

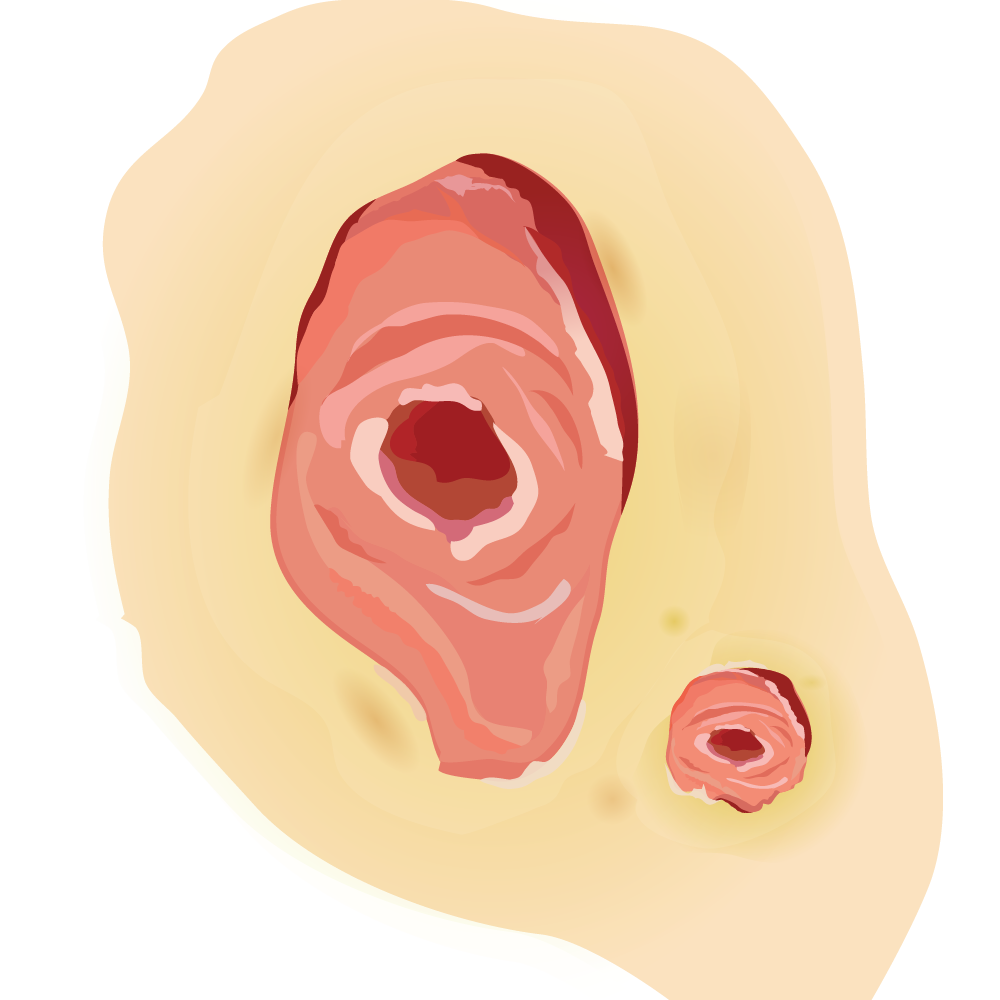

Pressure Injury Staging

Pressure injuries may never heal if the patient is failing to consume adequate food and fluids to maintain body functions and assist tissue growth.

An additional complication could be underlying involvement of the bone (known as osteomyelitis) in deep pressure injuries.

If osteomyelitis is not managed appropriately by a qualified physician, it may result in serious sequelae and the possibility of the wound never healing.

(It is a given that when managing pressure injury risk and actual damage, the pressure is relieved, and attention is given to nutritional requirements.)

There are now six classifications of pressure injury. Click through below to explore:

Leg Ulceration

Although there are many types of leg ulcers, the most common are venous, followed by arterial, and then mixed venous arterial.

The classic signs and symptoms of each of these ulcer types can be found in the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guideline for Venous ulcer prevention and management.

Ulceration of lower legs is often complex as the diagnosis may not have been made.

Venous ulcers can heal with compression therapy, however, conversely, some arterial ulcers may deteriorate if compression is used.

Therefore having a knowledge of the characteristics of venous and arterial ulcers is imperative to ensure appropriate decision-making regarding management of these wounds.

Venous Ulceration

Venous ulcers are located in the lower third of the lower leg and generally are superficial and weeping.

The priority of care is managing oedema and encouraging the epithelium to grow across the superficial break.

Zinc paste bandages and compression bandages are the mainstay of treatment to achieve these goals. The zinc paste bandages may include products like Viscopaste™ or Ichthopaste™.

If the wound has been present for a considerable length of time, then some bacterial involvement is likely, and so an antimicrobial is suggested, such as Iodosorb Powder™ or Sorbact compress™. This could then be combined with a super absorbent pad such as Zetuvit Plus™.

Compression therapy selection is complex and must be tailored to the patient. A safe and effective system from which to start, however, is the use of straight, elasticated tubular bandage, for example, Tubigrip™ or Tubular Form™.

These must be applied from toes to knee after selecting the appropriate size according to the manufacturer's guide. Commence with one layer, if tolerated, then add another second layer but extending to only 2/3 of the lower leg and finally, if tolerance is maintained, then add another 1/3. This is known as a 3-layer straight elasticated tubular bandage system, allowing the removal of the upper layers for sleeping, and reapplying the next morning.

Arterial Ulceration

When it comes to managing arterial ulceration, a vascular surgeon is best to consult as ideally, some surgery can be performed to restore perfusion to the limb. It then becomes the attending clinician’s role to prevent infection.

Generally, the rule is: if the tissue is dry and ischaemic, then keep it dry. So Betadine™ lotion is used to achieve this and keep the eschar dry.

If the tissue in the arterial wound is offensive, infected or malodourous, then a silver or cadexomer iodine may be used, such as Aquacel Ag™ or Iodosorb™ ointment/powder.

Keep your formulary up to date with what is considered best-practice and review the wound regularly to ensure progress.

Recognising and assessing a wound is an important part of providing healthcare.

Ultimately, however, the overall aim - for you, and for the patient - is to completely and successfully heal the wound.

The Healing Process

Most wounds go on to heal in the normal pathway of:

Inflammation

Proliferation

Epithelialisation

Maturation / Contraction

As there are many factors to consider when trying to manage a complex, slow-to-heal wound, the following factors are not an exhaustive list, and not necessarily presented in order of priority, however it is generally considered that nutrition is paramount in order to achieve healing.

Nutrition

Cellular growth is dependent on adequate intake of protein, vitamin C, zinc and iron. There are other nutrients required that also play an important role, but these four are often considered vital.

Protein

The formula to calculate a normal protein intake for a healthy adult woman is 0.75 g per kilogram of body weight per day, and 0.84 g per kilogram of body weight per day for healthy adult men. However, when a chronic non-healing wound is present or the individual is pregnant, breastfeeding, or over the age of 70 years, it increases to approximately 1-2 g per kilogram of body weight per day (National Health and Medical Research Council 2014).

Vitamin C

The recommended dietary intake (RDI) of vitamin C for a normal healthy adult is 45 mg per day, however, in an individual with a chronic wound, this increases to approximately 100-200 mg per day (NHMRC 2014).

Zinc

Normal RDI of zinc is 8 mg in healthy adult women, and 14 mg per day for adult men. However, as with protein and vitamin C, this increases to an RDI of 15-25 mg per day in individuals with a complex, slow-healing wound.

Iron

Iron intake is also necessary for wound healing. The RDI of iron is greater in women during the menstrual years, with 18 mg per day advised to support healthy functioning. For women greater than 51 years of age, and all healthy adult men, the intake is recommended to be 8 mg per day. To boost wound healing, however, and in women who are pregnant, the RDI for iron can be as high as 30 mg per day.

There is no doubt that a healthy, balanced diet of fresh fruit, vegetables, meat, fish and chicken is invaluable to keep the body functioning well.

Issues can arise in older adults who fail to fulfil the RDIs for the required nutrients, and this is when wounds in older adults may fail to heal due to lack of appropriate nutrients.

Other Factors

Additional factors that may influence healing include:

For a chronic wound to progress to the healing phase, healthcare professionals must be able to clean the wound as thoroughly as possible without causing further pain to the patient.

The words 'cleansing' and 'debridement' are often used interchangeably, however, they are two distinct terms to describe different management processes:

Wound Cleansing

The application of a fluid that is then wiped across the wound area with gentle strokes to aid in the removal of any loose, unwanted product or agent.

Wound Debridement

The removal of dead or devitalised tissue, particulate matter, and foreign bodies from a wound bed. Debridement is generally accepted as a necessary precursor to the formation of new tissue.

There are many methods of wound debridement; some are readily accessible to the majority of clinical staff, however, others require specialist training or application and may only be found in specialty clinics or acute care facilities.

Types of Debridement

Autolysis

The most common method of removing necrotic tissue from a wound is using the body’s own naturally occurring enzymes and fluid to breakdown and consume the unwanted cells. This is referred to as autolysis. Moist wound therapy assists in this process, although some moist agents can increase the risk of maceration.

Wound care dressing products that assist in aiding autolytic debridement include:

- Hydrogels - Water-insoluble agents that work by rehydrating the tissue, encouraging the body’s naturally-occuring macrophages to manage the autolysis.

- Hydrocolloids - Moisture-retentive dressings that work similarly to hydrogels.

- Cadexomer iodine - Sugar-based iodine that absorbs fluids and kills microorganisms.

- Enzyme alginogel - Breaks-down the unwanted tissue and kills microorganisms.

- PHMB - Polyhexamethylene biguanide prevents microorganisms from further-developing and aids in lifting debris from the wound bed.

- Antimicrobial-binding dressings - Attracts and absorbs microorganisms preventing them from reentering the wound.

- Isotonic dressings - Creates an unfavourable environment for microbial growth.

- Hypertonic saline - Pulls microorganisms away from the wound bed.

- Silver dressings - Silver is an antimicrobial agent.

Biological

Biological debridement uses specifically-bred larvae to phagocytose the necrotic tissue and aid in its removal. This process is not commonly used as patients are generally not comfortable with having maggots put on their wounds.

Chemical

Chemical agents for debridement are no longer available in Australia. Whilst there are some being used overseas, none of these have yet been approved for use in Australia.

Enzymatic

There are a few enzyme products available around the world but the only one currently available in Australia is Flaminal™. This product is a mixture of calcium alginate and two naturally occurring enzymes found in saliva-lactose peroxidase and glucose oxidase.

Mechanical

Mechanical debridement can involve several different methods. Sharp surgical is the gold-standard of mechanical debridement, and involves having a surgeon manually remove all of the necrotic tissue so that the vascular bleeding wound bed is exposed.

Conservative sharp wound debridement is the next best option, and is usually carried out by a skilled clinician such as a wound consultant or podiatrist.

Another mechanical method of debridement includes using a high-pressure irrigation device, which literally blows off the necrotic tissue.

By performing excellent gentle wound cleansing and debridement, healthcare professionals can assist with wound healing by removing any necrotic tissue which may be impacting the treatment goals.

Simple debridement that can be undertaken by all healthcare professionals involves gentle circular movements over the wound with dry gauze, which may lift some debris.

Using forceps to gently scrape the tissue may also help lift debris off the wound.

Naturally, all of these aforementioned methods require a thorough assessment of the patient and their pain both during and after the dressing procedure.

When managing a complex, slow-healing wound, it is important to remember that there are occasions when wound debridement is not appropriate, and symptom control is more suitable.

For example, dry eschar does not always need to be removed – in some cases it acts as its own dressing.

Should the body decide to separate the eschar from the tissue below it, the eschar then usually provides a well-demarcated edge from which to work.

It is imperative to ensure that the correct dressing, and dressing regime, has been chosen to optimise wound healing.

When your assessment reveals that the wound is heavily soiled, necrotic tissue is present, and/or there is the potential of bacterial colonisation, then more regular dressings will be required.

In many cases, these heavily colonised wounds will require daily dressing changes, with emphasis on peri-wound protection.

If the decision has been made to change a dressing daily, then consideration on product choice becomes imperative as costs will rise unless less expensive dressings are selected.

Once the necrotic tissue has been removed and healthy granulation tissue is present, the aim dramatically changes to one of protection.

The goal here is to disturb the tissue as little as possible, in order to allow the body to heal itself.

Products chosen at this time can remain in situ for four to five days, or even as long as seven days, depending on the absorbent capacity and nature of the wound interface material.

Foam dressings are usually the best product to achieve these parameters.

One of the crucial aspects of a dressing regime is assessment and reassessment.

Assessment at each dressing change involves looking for changes in tissue type and exudate volume and type, any reduction in odour, changes in wound size, and reduction of pain.

These will not occur simultaneously, so deciding which parameter to check each week will be left to the attending clinician. However, the most important signs to measure wound healing include improvements in tissue quality, and reduction of odour and exudate volume.

With continued best-practice interventions, these signs indicate that the wound will most likely go on to heal.

In evaluating the effectiveness of a treatment regime, the healthcare professional should be able to clearly state the wound type and what the treatment aims were.

Without establishing these factors, the aim/s and product selection are random and not based on best-practice recommendations.

Wounds that generally do not heal unless surgical/medical intervention is possible include arterial ulcers, skin cancers and tumours, and wounds as a result of an autoimmune disorder.

Dressings play a less significant role in the management of these wounds, and healing is almost totally dependent on managing the overarching problem.

- Australian Wound Management Association Inc. and the New Zealand Wound Care Society Inc. 2011, Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers, Cambridge Publishing, Australia, viewed 17 January 2023, https://www.woundsaustralia.com.au/...Management_of_Venous_Leg_U.aspx.

- Dowsett, C, Protz, K, Drouard-Segard, M & Harding, K 2015, Triangle of Wound Assessment Made Easy, Wounds International, London, UK, viewed 17 January 2023, https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/details/triangle-of-wound-assessment-made-easy.

- European Wound Management Association 2019, EMWA Position Documents (2002-2008), EWMA, Denmark, viewed 17 January 2023, https://ewma.org/resources/for-professionals/ewma-documents-and-joint-publications/ewma-position-documents-2002-2008/.

- European Wound Management Association 2019, EWMA documents and joint publications, EWMA, Denmark, viewed 17 January 2023, https://ewma.org/resources/for-professionals/ewma-documents-and-joint-publications.

- Leaper, DJ, Schultz, G, Carville, K, Fletcher, J, Swanson, T & Drake, R 2012, 'Extending the TIME concept: what have we learned in the past 10 years?', International Wound Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1-19, viewed 17 January 2023, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01097.x.

- Lipsky, BA & Hoey, C 2009, 'Topical Antimicrobial Therapy for Treating Chronic Wounds', Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 1541-9, viewed 17 January 2023, http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/49/10/1541.full.

- National Health and Medical Research Council 2017, Nutrient References Values for Australia and New Zealand: Nutrients, NHMRC, Canberra, viewed 17 January 2023, https://www.nrv.gov.au/nutrients.

- Swanson, T, Ousey, K, Haesler, E, Bjarnsholt, T, Carville, K, Idensohn, P, Keast, DH, Larsen nee Angel, D, Waters, N & Weird, D 2022, Wound Infection in Clinical Practice: Principles of Best Practice, 3rd edn, Wounds International, London, UK, viewed 17 January 2023, https://woundinfection-institute.com/resources/.

- Vowden, K & Vowden, P 2002, Wound Bed Preparation, World Wide Wounds, UK, viewed 17 January 2023, http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2002/april/Vowden/Wound-Bed-Preparation.html.

- Wound Healing and Management Node Group 2013, 'Wound Management: Debridement - Autolytic', Wound Practice and Research, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 94-5, viewed 17 January 2023, https://www.woundsaustralia.com.au/Web/Resources/Journal/Journal_Archive.aspx.

- Wounds International 2019, Best Practice, London, UK, viewed 17 January 2023, https://www.woundsinternational.com/resources/all/0/date/desc/cont_type/45.

New

New