Careful thought and creativity is as important to aged care menu planning as it is to the selection of our own daily meals - if not, more so, given the heightened health complications inherent with ageing.

When a person enters an aged care facility, their autonomy may have decreased significantly. One of the many choices an individual may mourn is the lack of choice in meal selection.

As aged care residents largely forfeit their say on the timing, duration, and environment of mealtimes, it only seems fair that they will want input into the type of meals they receive.

It is well known that food consumption and nutrition are closely linked to our overall quality of life. Studies have shown when residents have the agency to choose from a menu, levels of food service satisfaction rise by up to 30% (Abbey et al. 2015).

Increased independence in food choice and active participation in food planning have also been associated with a reduced risk of malnutrition (Abbey et al. 2015).

This article will provide broad nutritional advice for older people and outline methods of effective meal planning in aged care facilities.

Meal Planning Under the Strengthened Aged Care Quality Standards

Standard 6: Food and Nutrition under the strengthened Aged Care Quality Standards recognises that access to nutritionally appropriate food is a basic human right and emphasises the importance of providing flavourful, appetising and nutritious meals (ACQSC 2024).

- Work in partnership with older people to ensure food and drinks are enjoyable

- Continuously assess and improve the food service based on:

- Older people’s satisfaction with food and drinks

- Older people’s nutritional requirements

- Older people’s health outcomes

- Contemporary, evidence-based practice

- Assess each older person’s nutrition and hydration requirements and preferences

- Create menus that offer variety and meet nutritional needs

- Provide choices about what they eat and drink

- Ensure access to nutritious snacks and beverages

(ACQSC 2024)

For more information on meal planning under the strengthened Standards, see Ausmed’s Training Module on Standard 6: Food and Nutrition.

Malnutrition in Aged Care Facilities

There is an alarming trend of malnutrition among older people living in aged care facilities (ACQSC 2023).

One study conducted by the British Journal of Nutrition, which looked into the nutrient content of meals in Australian aged care facilities, found that 68% of participants were either malnourished or had the potential to become malnourished (Rossi 2017).

Older people are known to be at a disproportionate risk of malnutrition (Rossi 2017). There are many reasons for this, including:

- Decreased food intake due to factors such as isolation and reduced ability to access food

- Physical impairment such as disability, reduced appetite, reduced sense of taste or smell, difficulty chewing or swallowing, difficulty self-feeding or difficulty preparing food

- Cognitive and psychological issues such as dementia, depression, anxiety, self-neglect and bereavement

- Being unable to consume certain food groups due to difficulty chewing, swallowing or digesting

- Polypharmacy, which may impair nutrient absorption or increase nutrient loss

- Having a poor eating environment

- Inflammation associated with disease, injury or illness

- Requiring assistance with eating due to factors such as cognitive impairment

- Being unable to consume sufficient amounts of food.

(TAS DoH 2020; Rossi 2017; Iuliano-Burns 2023)

Preventing and Treating Malnutrition

- Dietary approaches:

- Ensuring sufficient energy and nutrient quality through meals and food between meals

- Food fortification:

- Improving the nutritional density of meals

- Can be used as a vehicle for nutrients, for example, adding vitamin D to foods

- Oral nutritional supplements (protein supplements):

- Found to be particularly effective in hospital settings

- Potentially less effective in aged care settings.

(Iuliano-Burns 2023)

Feeding Assistance

Feeding assistance is one method to curb malnutrition in older people. The level of assistance required by people will vary. Assistance can range from:

- Supervision, prompting, and encouragement

- Setting up cutlery etc.

- Cutting up meals

- Full feeding assistance.

(Eat Well Nutrition 2014)

The style and manner of feeding assistance are important to get right. Staff must be trained to feed in a controlled manner, distractions should be minimised, altered utensils should be made available, and swallowing rehabilitation is to be encouraged if appropriate (Iuliano-Burns 2023).

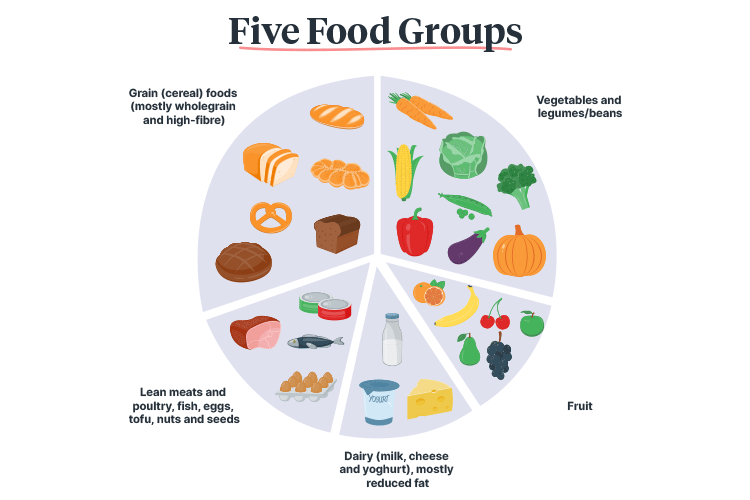

A Dietary Guide for the Older Person

Our dietary needs change as we age. It is important to know how much and what type of food a person should be eating in accordance with their age and gender.

Note: These recommended servings are for older adults aged over 65. For a comprehensive list of servings based on age and gender, see the National Health and Medical Research Council’s Australian Dietary Guidelines Summary.

| Food group | Daily servings (males) | Daily servings (females) | Examples of one serving |

|---|---|---|---|

Vegetables, legumes and beans Choose a variety of types and colours (e.g. green, orange, red, yellow, purple and white) |

5 | 5 |

|

Fruits |

2 | 2 |

|

Grains (mostly wholegrain and high-fibre) |

4½ | 3 |

|

Lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds |

2½ | 2 |

|

Dairy products or alternatives |

4 | 3½ |

|

(Better Health Channel 2017; NHMRC 2013)

Other Considerations

- Unnecessary dietary restrictions (e.g., on sugar and fat) can lead to malnutrition - instead, focus on optimising the enjoyment of food

- Drink plenty of water (six to eight cups every day)

- High fibre and water intake will assist movement in slow bowels

- Eating fish regularly can reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke, dementia, and macular degeneration

- Some older people may benefit from vitamin or mineral supplements if they have a diagnosed deficiency, however, these are not to be taken simply to compensate for a poor diet.

(Abbey et al. 2015; CCLHD 2015; Better Health Channel 2017; Nutrition Australia 2021)

Nutrient Requirements for Older People

Increased intake of the following nutrients is recommended for older people. Keep these requirements in mind for all meal planning:

- Calcium

- Vitamin D

- Vitamin B12

- Fibre

- Fats (polyunsaturated and monounsaturated).

(Klemm 2023; Better Health Channel 2017)

Meal Planning

We eat with our eyes first, which means that the visual appearance of a meal matters. Make sure to incorporate a wide variety of colours, textures, flavours, and types of food to keep things interesting in aged care meal planning (Comcater 2023).

While rotational meals are doubtless a more convenient option in aged care facilities, keep in mind the importance of meal variation on resident nutritional needs and meal enjoyment.

Meal Examples

Breakfast

- Cereal with added yoghurt and fruit

- Nut-based spread, egg, or sardines on wholegrain toast.

Lunch

- An open sandwich with cheese, ham, tuna/sardines accompanied by milk or banana smoothie

- Vegetable cheese frittata with salad

- White bean soup with vegetables and/or chorizo.

Dinner

- Grilled white fish or salmon with sauce, potatoes and vegetables

- Moroccan chickpea vegetable casserole

- Slow-cooked beef casserole with gravy and vegetables

- Creamy pasta with vegetables.

Dessert

- Ice-cream, yoghurt, or custard with fruit.

(Better Health Channel 2017; Pro Portion Foods 2018)

Meal Planning Considerations

Some residents have specific meal requirements. When planning meals, always take into account the following:

- Medical needs

- Allergies and intolerances

- Dietary restrictions (e.g., vegetarian)

- Eating and swallowing capabilities

- Cultural customs

- Religious food practices

- Mental illness

- Personal likes and dislikes

- Medicines being taken

- Additional energy requirements (e.g., due to unplanned weight loss, illness, or injury)

- Overweight and obesity.

(Metro South Health 2018)

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

What should aged care facilities provide to support the dietary needs of older people according to the strengthened Aged Care Quality Standards?

Topics

Further your knowledge

Free

Free Free

Free

References

- Abbey, KL, Wright, OR and Capra, S 2015, ‘Menu Planning in Residential Aged Care-The Level of Choice and Quality of Planning of Meals Available to Residents’, Nutrients, vol. 7, no. 9, viewed 29 April 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4586549/

- Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission 2023, Analysis of a Survey of Food and Dining Experiences in Residential Aged Care Services - Final Report, Australian Government, viewed 29 April 2024, https://www.agedcarequality.gov.au/resource-library/analysis-survey-food-and-dining-experiences-residential-aged-care-services-final-report

- Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission 2024, Standard 6: Food and Nutrition, Australian Government, viewed 30 April 2024, https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/strengthened-aged-care-quality-standards-august-2025?language=en/food-and-nutrition

- Better Health Channel 2017, Nutrition Needs When You’re Over 65, Victoria State Government, viewed 30 April 2024, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/healthyliving/Nutrition-needs-when-youre-over-65

- Central Coast Local Health District 2015, Best Practice Food and Nutrition Manual for Aged Care, New South Wales Government, viewed 30 April 2024, https://www.cclhd.health.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/BestPracticeFoodandNutritionManualforAgedCare.pdf

- Comcater 2023, What Makes a Great Aged Care Menu?, Comcater, viewed 29 April 2024, https://www.comcater.com.au/blog/what-makes-a-great-aged-care-menu/

- Eat Well Nutrition 2014, Educational Video 4: Feeding Assistance, Eat Well Nutrition, online video, viewed 29 April 2024, https://www.eatwellnutrition.com.au/2014/09/10/educational-video-4-feeding-assistance/

- Iuliano-Burns, S 2023, 'Malnutrition in the Older Adult', Ausmed, 12 March, viewed 29 April 2024, https://www.ausmed.com/cpd/courses/older-malnutrition

- Klemm, S 2023, Eat Right for Life, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, viewed 30 April 2024, https://www.eatright.org/health/wellness/healthful-habits/eat-right-for-life

- Metro South Health 2018, A Toolkit for Healthy Eating in Supported Accommodation: A Best Practice Guide, 2nd edn, Queensland Government, viewed 30 April 2024, https://metrosouth.health.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/supported-accommodation-toolkit.pdf

- National Health and Medical Research Council 2013, Australian Dietary Guidelines: Summary, Australian Government, viewed 30 April 2024, https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n55a_australian_dietary_guidelines_summary_130530.pdf

- Nutrition Australia 2021, Nutrition and Older Adults, Nutrition Australia, viewed 30 April 2024, https://nutritionaustralia.org/fact-sheets/nutrition-and-older-adults-2/

- Pro Portion Foods 2018, Nutrition For Active And Healthy Ageing, Pro Portion Foods, viewed 30 April 2024, http://www.proportionfoods.com.au/menu-planning-in-aged-care-qa-with-a-dietitian/

- Rossi, A 2017, ‘Older People at Disproportionate Risk of Malnutrition’, Aged Care Guide, 30 May, viewed 29 April 2024, https://www.agedcareguide.com.au/talking-aged-care/older-people-are-often-at-disproportionate-risk-of-malnutrition

- Tasmania Department of Health 2020, Malnutrition, Tasmanian Government, viewed 29 April 2024, https://www.dhhs.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/343372/Malnutrition_background.pdf

New

New