Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of skin cancer but the least serious (SunSmart 2014).

If addressed early, BCC can be easily resolved in most cases (Cancer Council Australia 2021).

Non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), which comprises BCC and squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) (along with very rare skin cancers such as Merkel cell carcinoma), is the most common type of cancer in Australia and accounts for about 98% of all skin cancer cases (Cancer Council Australia 2021).

BCC has several features distinguishing it from cSCC and melanoma. Awareness of these differences can assist with timely referral and treatment, thereby reducing morbidity associated with aggressive tumours and enhancing overall patient outcomes. All healthcare professionals should be able to identify lesions and refer appropriately.

What is Basal Cell Carcinoma?

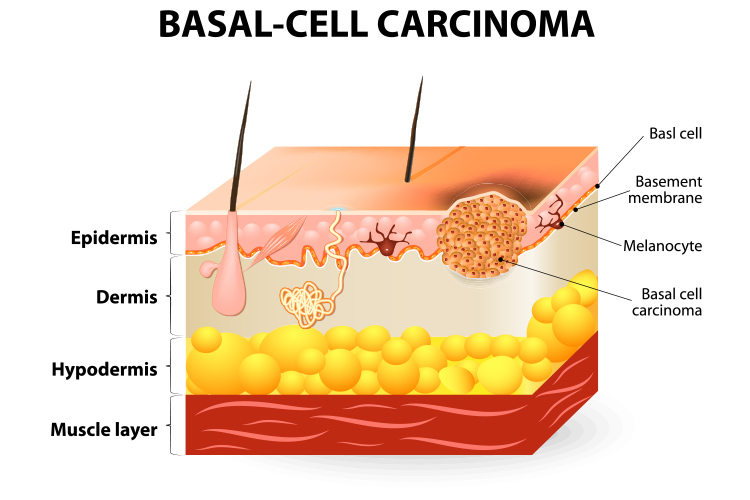

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is triggered by DNA mutation (caused by UV radiation, usually from the sun) to the block-like basal cells located in the lower layer of the epidermis, which causes the cells to grow and change abnormally (Skin Cancer Foundation 2022; Cancer Council Victoria 2022).

BCC has a comparatively slow growth rate to cSCC, usually developing over several months or years, and rarely spreads to other areas of the body. It is possible for BCCs to grow rapidly or metastasise, but this is a rare occurrence (Cancer Council Australia 2021; Oakley 2015).

NSMCs as a whole have a low mortality rate of about 1.9 deaths per 100,000 patients (Khong et al. 2020).

Despite this, neither patients nor healthcare staff should be complacent when addressing any kind of skin cancer as it is possible for an untreated BCC to grow deeper into the skin and cause tissue damage, complicating treatment (Khong et al. 2020; Cancer Council Australia 2021).

A past history of BCC increases the likelihood of developing another BCC, with approximately 50% of patients developing a new lesion within three years of treatment. An individual can also have more than one BCC simultaneously (Oakley 2015; Cancer Council Australia 2021).

BCCs can develop anywhere on the body but are most commonly found in areas that receive frequent sun exposure, including the:

- Head

- Face

- Neck

- Shoulders

- Back

- Lower arms

- Lower legs.

(Cancer Council Victoria 2022)

Prevalence of Basal Cell Carcinoma

BCC accounts for about 66% of skin cancers in Australia. It is most common in those over 40 years of age but can affect anyone (Cancer Council Australia 2021).

In 2020, the total number of mortalities from NMSCs (including BCCs, cSCCs and other rare cancers) was 722 (Cancer Council Australia 2022).

Warning Signs of Basal Cell Carcinoma

There are over 26 subtypes of BCC (McDaniel et al. 2022), but the most common is nodular BCC, which accounts for more than 60% of cases. It commonly presents as a shiny, firm, dome-shaped nodule ranging from a few millimetres to several centimetres in diameter. It is generally pearly, pink, skin-coloured or translucent in colour with a smooth surface. It may bleed or ulcerate spontaneously, then form a scab and appear to heal like a normal wound (Bader 2022; Oakley 2015; Wells 2022).

Other common types of BCC include:

- Superficial BCC: Usually presents as a flat and slightly scaly red or pink patch. It is most commonly found on the upper trunk or shoulders, grows slowly and is not overly aggressive.

- Morpheaform BCC: Usually presents as a flat white, yellow or waxy lesion resembling a scar. Accounts for about 10% of lesions.

(McDaniel et al. 2022)

Risk Factors for Basal Cell Carcinoma

- Older age (older males are particularly at risk)

- Fair complexion (particularly if the individual has freckles, blonde or red hair or blue or green eyes)

- History of skin cancer (BCC or another type)

- Unprotected UV exposure (either from the sun or artificial sources)

- History of sunburns

- Family history of skin cancer

- Exposure to arsenic

- Reduced immune function due to illness or immunosuppressive medications

- Certain genetic conditions.

(Cancer Council Australia 2021; Oakley 2015)

Diagnosis of Basal Cell Carcinoma

BCCs can be diagnosed through physical examination and biopsy if required. They rarely require staging (Wells 2022; Cancer Council Australia 2021).

Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma

If detected early, BCCs can almost always be treated successfully. The treatment method will depend on the specific lesion, however, surgical excision is usually the most appropriate choice. Sometimes a biopsy will have already removed the entirety of the cancer. Other options include:

- Curettage and electrocautery

- Cryotherapy

- Photodynamic therapy

- Imiquimod (immunotherapy) cream

- Fluorouracil (chemotherapy) cream

- Radiotherapy.

(Wells 2022; Oakley 2015; Cancer Council Australia 2021)

Advanced, recurrent or metastatic BCCs may require a combination of surgery, radiotherapy, targeted therapies or other treatments (Oakley 2015).

Due to the likelihood of developing another BCC, melanoma or other skin cancer post-treatment, patients are encouraged to undergo annual skin checks (Oakley 2015).

Conclusion

Although BCCs are usually easy to treat and are not overly aggressive, they should be addressed early in order to reduce the likelihood of complications, and patients should be regularly assessed post-treatment to ensure any new skin cancers are quickly resolved.

Being able to identify and appropriately respond to BCCs is not only integral to treatment, but also ensures lesions can be differentiated from more aggressive and dangerous cancers that require urgent action.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

What is the most common type of BCC?

Topics

References

- Anand, RL, Collins, D & Chapman, A 2017, ‘Basosquamous Carcinoma: Appearance and Reality’, Oxf Med Case Reports., no. 1, viewed 22 August 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5209554/

- Bader, RS 2022, Basal Cell Carcinoma Questions & Answers, Medscape, viewed 22 August 2023, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/276624-questions-and-answers

- Cancer Council Australia 2022, Skin Cancer Incidence and Mortality, Cancer Council Australia, viewed 22 August 2023, https://wiki.cancer.org.au/skincancerstats/Skin_cancer_incidence_and_mortality

- Cancer Council Australia 2021, Understanding Skin Cancer, Cancer Council Australia, viewed 22 August 2023, https://www.cancer.org.au/assets/pdf/understanding-skin-cancer-booklet

- Cancer Council Victoria 2022, Skin Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria, viewed 22 August 2023, https://www.cancervic.org.au/cancer-information/types-of-cancer/skin_cancers_non_melanoma/skin-cancer-overview.html

- Khong, J, Gorayski, P & Roos, D 2020, ‘Non-melanoma Skin Cancer in General Practice: Radiotherapy is an Effective Treatment Option’, Australian Journal of General Practice, vol. 49 no. 8, viewed 22 August 2023, https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2020/august/nonmelanoma-skin-cancer-in-general-practice

- McDaniel, B, Badri, T & Steele, RB 2022, ‘Basal Cell Carcinoma’, StatPearls, viewed 22 August 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482439/

- Oakley, A 2015,

Basal Cell Carcinoma, DermNet, viewed 22 August 2023, https://dermnetnz.org/topics/basal-cell-carcinoma/ - Skin Cancer Foundation 2022, Basal Cell Carcinoma Overview, Skin Cancer Foundation, viewed 22 August 2023, https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/basal-cell-carcinoma/

- SunSmart 2014, About Skin Cancer, SunSmart, viewed 22 August 2023, https://www.sunsmart.com.au/skin-cancer/about-skin-cancer

- Wells, GL 2022, Basal Cell Carcinoma, MSD Manual, viewed 22 August 2023, https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-au/home/skin-disorders/skin-cancers/basal-cell-carcinoma

New

New