About 219,800 Australians are estimated to be living with chronic hepatitis B (Matthews & Elliot 2025).

Despite this, hepatitis B is a largely preventable condition.

What is Hepatitis B?

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that causes inflammation of the liver. It develops upon being infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is one of the five main hepatitis viruses along with types A, C, D and E (Healthdirect 2024a).

Upon entering the body, the HBV virus multiplies in the liver, triggering an immune response that damages and kills the hepatocytes (liver cells) (AMBOSS 2025).

Hepatitis B is a serious condition that has the potential to cause long-lasting damage and complications. While there is no cure, symptoms can be managed and, in many cases, will resolve on their own. However, some people with hepatitis B become chronically ill (Healthdirect 2024b).

What’s the Difference Between Hepatitis B and Other Hepatitis Viruses?

It’s important to remember that hepatitis A, B, C, D and E are different illnesses caused by different viruses. While they all cause liver infection, they are not the same and should not be treated as interchangeable (WHO 2019).

- Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is transmitted via exposure to the faeces of an infected person, usually through close direct contact or consumption of contaminated food or water. A vaccine is available.

- Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is usually spread via percutaneous exposure to the blood of an infected person. This most commonly occurs through sharing needles and injecting drug equipment. Sexual transmission is possible but less likely. There is no vaccine to prevent hepatitis C.

- Hepatitis D virus (HDV) can only occur in those who have hepatitis B, either alongside HBV as a co-infection or as a ‘super-infection’.

- Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is transmitted via exposure to the faeces of an infected person or animal, usually through the consumption of contaminated food or water. It is more common in developing countries.

(WHO 2019; CDC 2020; Better Health Channel 2023a)

Among these types of hepatitis, A, B and C are the most common in Australia (Better Health Channel 2023a).

How Does Hepatitis B Spread?

HBV is found in body fluids - primarily blood, along with semen, vaginal secretions, menstrual fluids and saliva (Better Health Channel 2023b; WHO 2025).

The virus is spread by infectious body fluids entering the body via percutaneous (a puncture through the skin), mucosal (through the mucus membranes) or non-intact skin exposure (CDC 2020).

A person with acute hepatitis B is contagious as long as the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is present in their blood, which is usually for a period of four to five months. Those with chronic hepatitis B are usually contagious for the rest of their life (AIH 2023).

Ways that HBV can spread include:

- Unprotected sex with an infected person

- Sharing needles or piercing equipment with an infected person

- Sharing toothbrushes or razors with an infected person

- Perinatal transmission (a pregnant person with HBV spreading the virus to their baby)

- A human bite from an infected person

- During exposure-prone medical procedures

- Needlestick injuries

- Via organ transplantation or dialysis

- Exposure to open sores on an infected person

- Other exposure to the body fluids of an infected person.

(DoHDaA 2025; WHO 2025; CDC 2020)

Note that HBV cannot be transmitted via sharing food, drinks and eating utensils with someone who has the virus (Cancer Council NSW 2020).

Between 30 and 40% of hepatitis B infections have no known cause (Better Health Channel 2023b).

HBV is able to survive outside the body for seven days or more and can still infect others during this timeframe (WHO 2025).

Risk Factors for Hepatitis B

Those who are more at risk of being infected by HBV or developing chronic disease include:

- Infants

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Immunocompromised people (e.g. those living with HIV, those with impaired renal function, those on dialysis, those about to receive a solid organ transplant and those who have received a haematopoietic stem cell transplant)

- People living with hepatitis C

- People with chronic liver disease

- Preterm and low-birthweight neonates

- People who receive blood products

- People living with developmental disability

- People with occupations that increase their risk of acquiring hepatitis B (e.g. healthcare workers, police officers, armed forces members, emergency services staff, correctional facility workers, carers for people with developmental disability, funeral workers, embalmers, tattoo artists and body piercers)

- Babies born to birthing parents who are HBsAg positive

- Close contacts and sexual contacts of people with hepatitis B

- Men who engage in sexual intercourse with men

- Migrants from areas of the world that are hepatitis B-endemic, including North-East Asia, South-East Asia, Mediterranean Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, the Pacific Islands and Sub-Saharan Africa.

- People who use injection drugs

- Correctional facility inmates

- Sex workers.

(AIH 2023; Better Health Channel 2023b)

Symptoms of Hepatitis B

The incubation period of hepatitis is typically between 45 and 180 days after contracting the HBV virus (AIH 2023).

Many HBV infections are asymptomatic, particularly in young children and infants. Only about 30 to 50% of adults and 10% of children will develop symptoms (AIH 2023; SA Health 2024).

Those who are symptomatic may experience:

- Fever

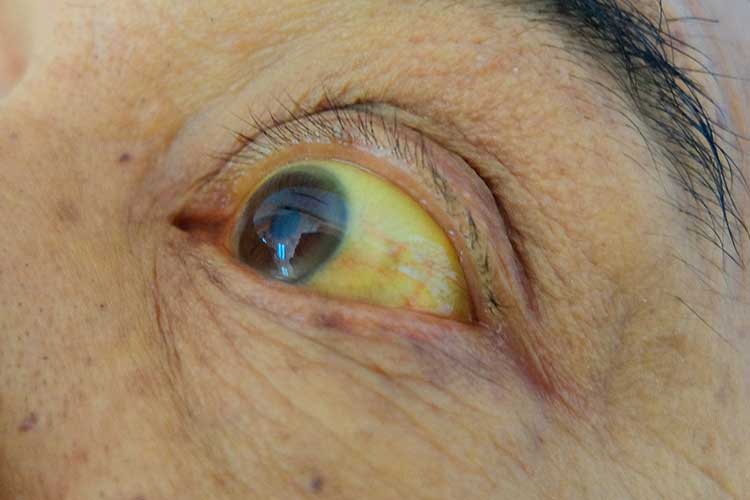

- Jaundice

- Fatigue

- Reduced appetite

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abdominal pain, particularly on the right side of the body under the ribcage

- Muscle pain and tenderness

- Urine that is dark in colour

- Stools that are light in colour

- Joint pain

- Arthritis

- Rash.

(AIH 2023)

These symptoms are typically the same as those caused by other types of hepatitis (AIH 2023).

An acute hepatitis B infection persists for up to six months (SA Health 2024).

Chronic Hepatitis B

Following an acute episode of hepatitis B, there is a risk that the patient will become chronically infected with HBV. This occurs very rarely in adults but is a common complication for infants (AIH 2023).

The likelihood of chronic hepatitis B developing is as follows:

| Age of exposure to HBV | Acute hepatitis B | Chronic hepatitis B |

|---|---|---|

| Infants < 1 year of age | Most patients will not experience acute symptoms | 90% of patients will develop chronic hepatitis B (if unvaccinated) |

| Children aged 1 to 6 | Most patients will not experience acute symptoms | 30% of patients will develop chronic hepatitis B |

| Adults and children aged over 6 | Most patients will experience acute symptoms | Up to 10% of patients will develop chronic hepatitis B |

(Adapted from Hepatitis Australia 2022; AIH 2023)

Therefore, adults are more likely to experience symptomatic acute hepatitis B but are less likely to develop chronic hepatitis B, while children are less likely to experience symptomatic acute hepatitis B but are much more likely to develop chronic hepatitis B.

While many people living with chronic hepatitis B are asymptomatic, they are at increased risk of complications such as cirrhosis (liver scarring) and liver cancer that may develop later on in life without any previous signs of ill health (Better Health Channel 2023b). These complications pose a high risk of death (WHO 2025).

People living with chronic hepatitis B are also still infectious to others and may not be aware that they are carrying the virus (AIH 2023).

Groups with a high prevalence of chronic hepatitis B in Australia include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and those born overseas (Matthews & Elliot 2025).

Diagnosing Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is diagnosed with blood tests to detect the presence of HBsAg (WHO 2025).

All pregnant people are recommended to be tested for hepatitis B due to the high risk of perinatal transmission (Better Health Channel 2023b).

Treatment of Hepatitis B

As there is no specific cure for hepatitis B, treatment involves symptom management and rest. Acute hepatitis B will eventually resolve on its own (Healthdirect 2024b).

Asymptomatic people living with chronic hepatitis B often do not require treatment but will need routine check-ups to monitor their liver for damage. Those who have signs of liver damage may require antiviral medicines and regular screening for liver cancer (SA Health 2024).

Preventing Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B Vaccine

The best way to prevent hepatitis B is through vaccination against the HBV virus. Immunisation is recommended for all infants and high-risk groups of people (those listed under the ‘Risk Factors for Hepatitis B’ section above) (Better Health Channel 2023b).

Under the National Immunisation Program, some groups are eligible for free immunisation against HBV (Better Health Channel 2023b).

95% of people who have received a full HBV vaccination course will be protected from hepatitis B (Healthdirect 2024b).

You can find more information about the hepatitis B vaccine in the Australian Immunisation Handbook.

Other Prevention Strategies

- Having protected sex using condoms

- Avoiding oral sex if one party has herpes, ulcers or bleeding gums

- Covering open wounds and cuts with waterproof dressings

- Avoiding sharing toothbrushes and razors with others

- Only getting tattoos and body piercings from registered studios that properly sterilise their equipment

- Avoiding sharing injection drug equipment and always ensuring needles and syringes have been sterilised

- Wearing disposable gloves if providing first aid or making contact with blood or body fluids.

(DoHDaA 2025; Better Health Channel 2023b)

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

Which type of hepatitis cannot be contracted on its own?

Topics

Further your knowledge

Free

Free Free

Free Free

Free Free

Free Free

FreeReferences

- AMBOSS 2025, Hepatitis B, AMBOSS, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.amboss.com/us/knowledge/Hepatitis_B

- Australian Immunisation Handbook 2023, Hepatitis B, Australian Government, viewed 29 May 2025, https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/vaccine-preventable-diseases/hepatitis-b

- Better Health Channel 2023a, Hepatitis, Victoria State Government, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/hepatitis

- Better Health Channel 2023b, Hepatitis B, Victoria State Government, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/hepatitis-b

- Cancer Council NSW 2020, What is Hepatitis B?, Cancer Council NSW, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.cancercouncil.com.au/cancer-prevention/screening/hepatitis-b-and-liver-cancer/what-is-hepatitis-b/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020, The ABCs of Hepatitis – For Health Professionals, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/resources/professionals/pdfs/abctable.pdf

- Department of Health, Disability and Ageing 2025, Hepatitis B, Australian Government, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.health.gov.au/diseases/hepatitis-b

- Healthdirect 2024a, Hepatitis, Australian Government, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/hepatitis

- Healthdirect 2024b, Hepatitis B, Australian Government, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/hepatitis-b

- Hepatitis Australia 2022, What is Hepatitis B?, Hepatitis Australia, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.hepatitisaustralia.com/what-is-hepatitis-b

- Matthews, G & Elliot, S 2025, ‘Prevalence and Epidemiology of Hepatitis B’, B Positive|Hepatitis B for Primary Care, viewed 29 May 2025, https://hepatitisb.org.au/prevalence-and-epidemiology-of-hepatitis-b/

- SA Health 2024, Hepatitis B - Including Symptoms, Treatment and Prevention, Government of South Australia, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/conditions/infectious+diseases/hepatitis/hepatitis+b+-+including+symptoms+treatment+and+prevention

- World Health Organisation 2019, Hepatitis, WHO, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/hepatitis

- World Health Organisation 2025, Hepatitis B, WHO, viewed 29 May 2025, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b

New

New