Pressure injuries may never heal if the patient does not consume adequate food and fluids to maintain body functions and assist tissue growth.

An additional complication could be underlying involvement of the bone (known as osteomyelitis) in deep pressure injuries.

If osteomyelitis is not managed appropriately by a qualified physician, it may result in serious sequelae and the possibility of the wound never healing.

(It is a given that when managing pressure injury risk and actual damage, the pressure is relieved, and attention is given to nutritional requirements and offloading or reducing the pressure on the area as much as possible.)

There are six classifications of pressure injury.

Pressure Injury Staging

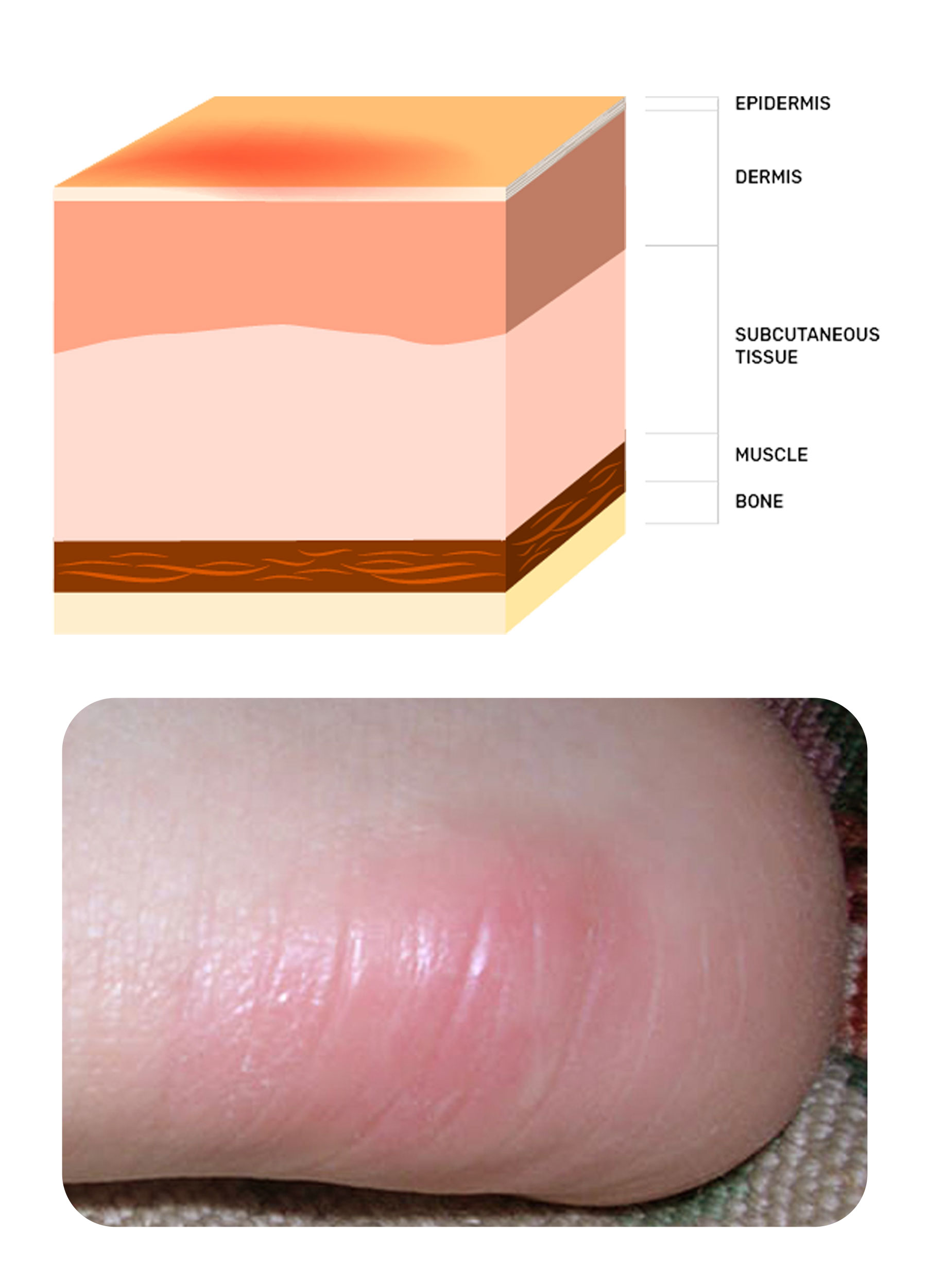

Stage One

Intact skin with non-blanchable redness of a localised area, usually over a bony prominence. In dark-skinned people, blanching is difficult to observe, so other parameters are looked for. These include bogginess, heat, pain, firmness and ‘blue’ discolouration of the skin.

A stage one pressure injury is an intact area of damage, so protecting the tissue and providing an environment for recovery is the aim.

Adhesive foams can be employed if moisturising the area on each shift isn’t possible. Examples of adhesive foam include Mepilex Border™, Biatain Silicone™ and Allevyn Life™.

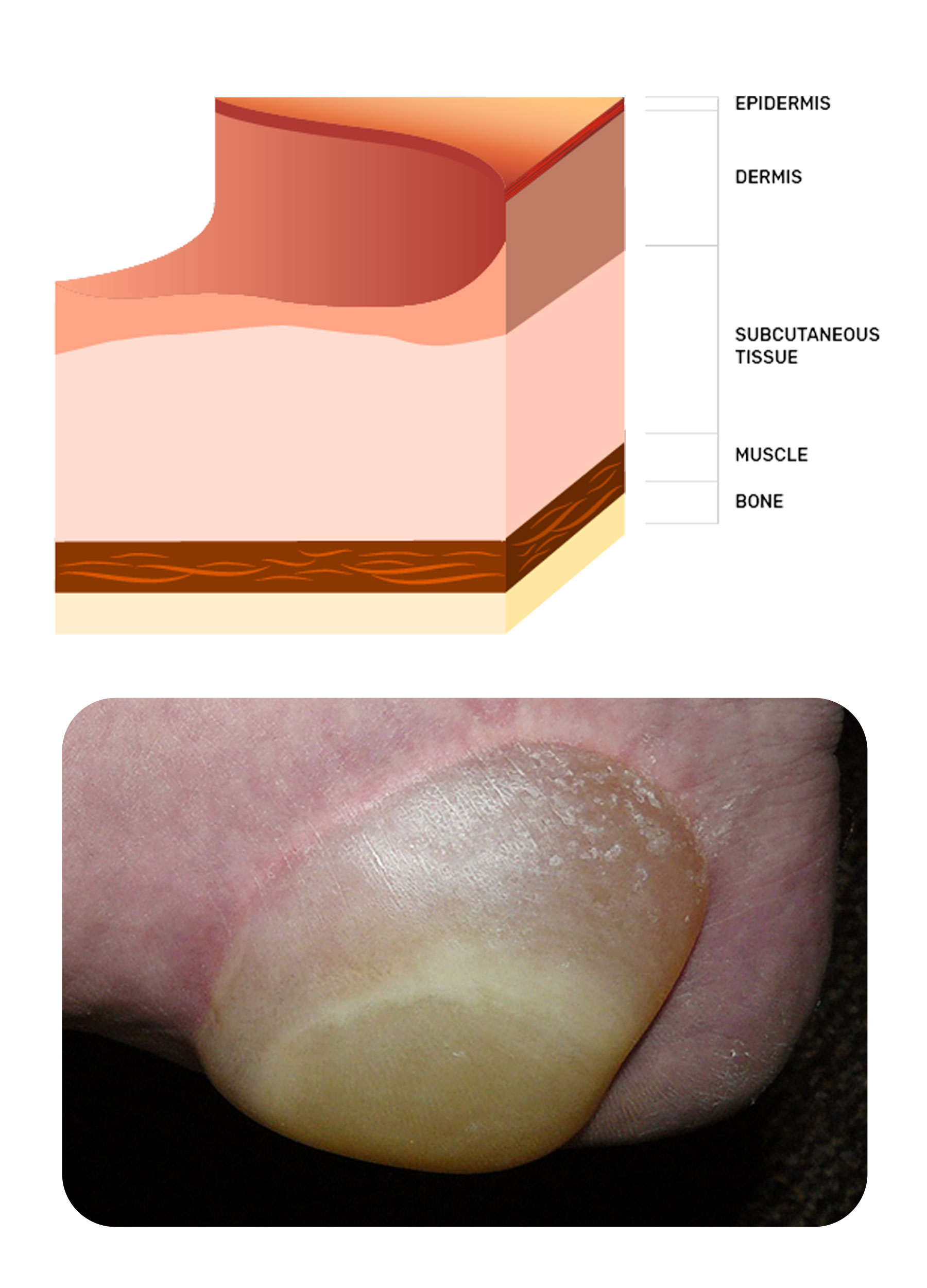

Stage Two

Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow, open wound with a red/pink wound bed, without slough or bruising. It may also present as an intact or ruptured serum-filled blister. Shiny or dry.

Stage two pressure injuries are relatively clean, superficial, partial-thickness injuries. Once again, protection is important; however, due to the break in the integument, the chosen dressing must also have some absorbent capabilities.

Adhesive foams are generally appropriate here unless the wound is located very close to the anus, in which case a thick barrier cream is often used. Conveen Critic Barrier Cream™, Secura Plus™ and Molicare Barrier Cream™ are appropriate examples.

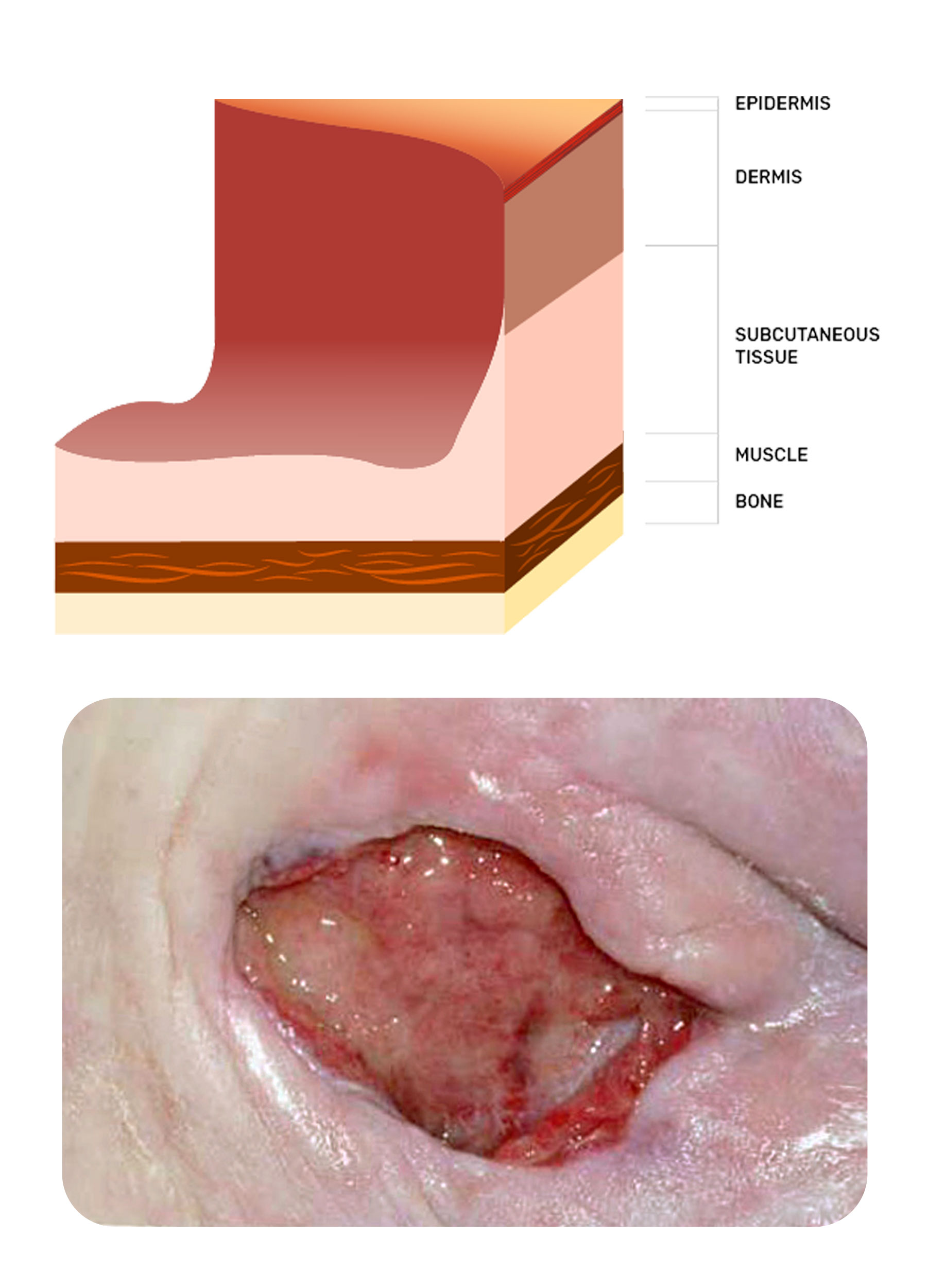

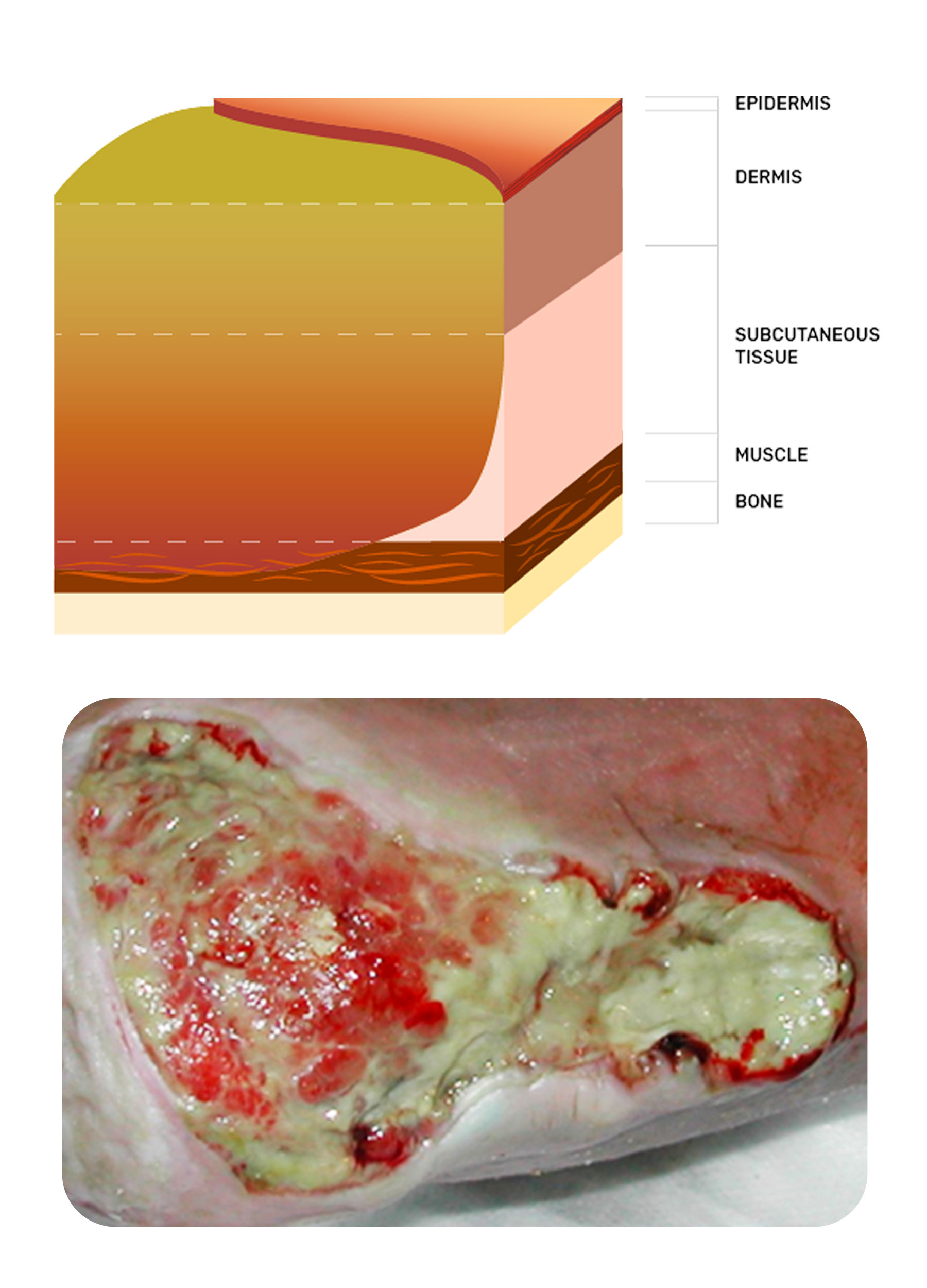

Stage Three

Full-thickness tissue loss; subcutaneous fat may be visible; slough may be present.

Stage three injuries involve damage through to the subcutaneous tissue, with the presence of slough and soft, tenacious necrotic tissue, which will require debridement.

Debridement can be managed by a surgeon or a skilled clinician, or dressings can be used to aid autolytic processes. Dressings that aid this autolysis include Flaminal Hydro or Forte™, Prontosan Gel™, Mesalt™ and Iodosorb™ powder or ointment. There are also pads available from companies that have varying levels of ‘roughness’, which enable you to massage the pad over the area and breakdown the debris you are wanting to remove from the area - Debrisoft pad™, Debridement pad™ and Alprep Pad™ are some examples.

Whilst the autolytic process is taking place, the wound exudate will be higher in volume, so super absorbent pads will be required as the secondary dressing. Examples of these include Zetuvit Plus™, Vliwasorb™ and Mextra™.

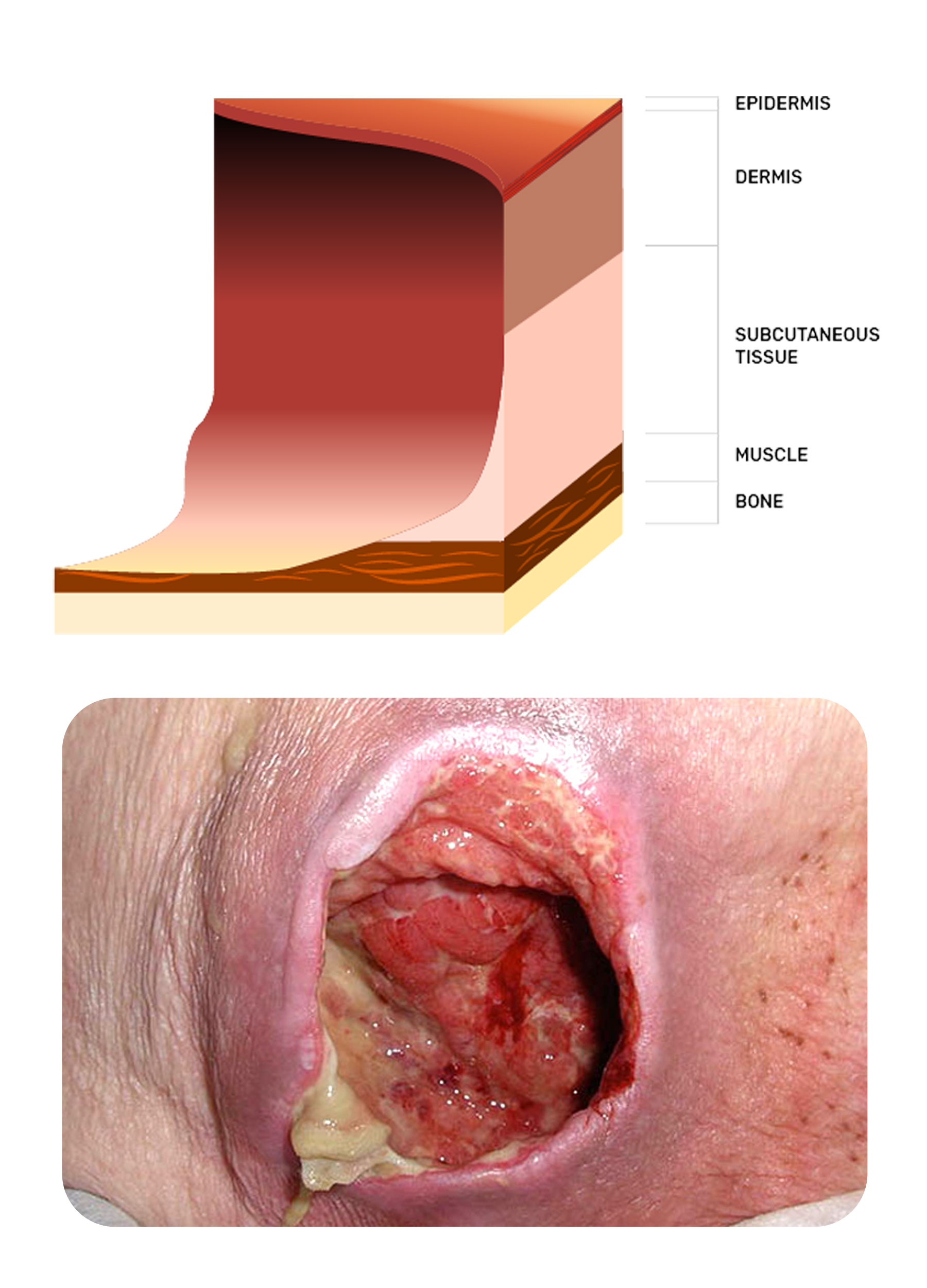

Stage Four

Full-thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present.

Stage Four implies that the area of damage extends down through muscle, and bone may be exposed or palpable. These injuries are generally necrotic and malodourous. Managing odour becomes the priority.

Metronidazole Gel™ will typically reduce odour in a few days. The cheaper version of metronidazole gel is Zidoval Vaginal Gel™. HydroClean Plus™ is a preloaded pack of polymer beds containing polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) that slowly drips into the wound, aiding autolytic debridement, and can safely be used with Metronidazole Gel™.

If the patient is in otherwise good health, then surgery and topical negative pressure devices would be used.

Unstageable (Depth Unknown)

Unstageable pressure injury (depth unknown): full thickness tissue loss, base is covered by slough and/or eschar (yellow/brown/black) in the injury bed.

The aim here is to remove the necrotic tissue until viable tissue is reached and the wound can begin to heal from the base up. Clinicians often panic when the wound is getting deeper - it is important to remember that it was classified as unstageable because there was no ability to measure the depth. Therefore, getting deeper when removing the necrotic tissue is to be expected - it is not a complication!

Debriding products previously mentioned can be used in this category.

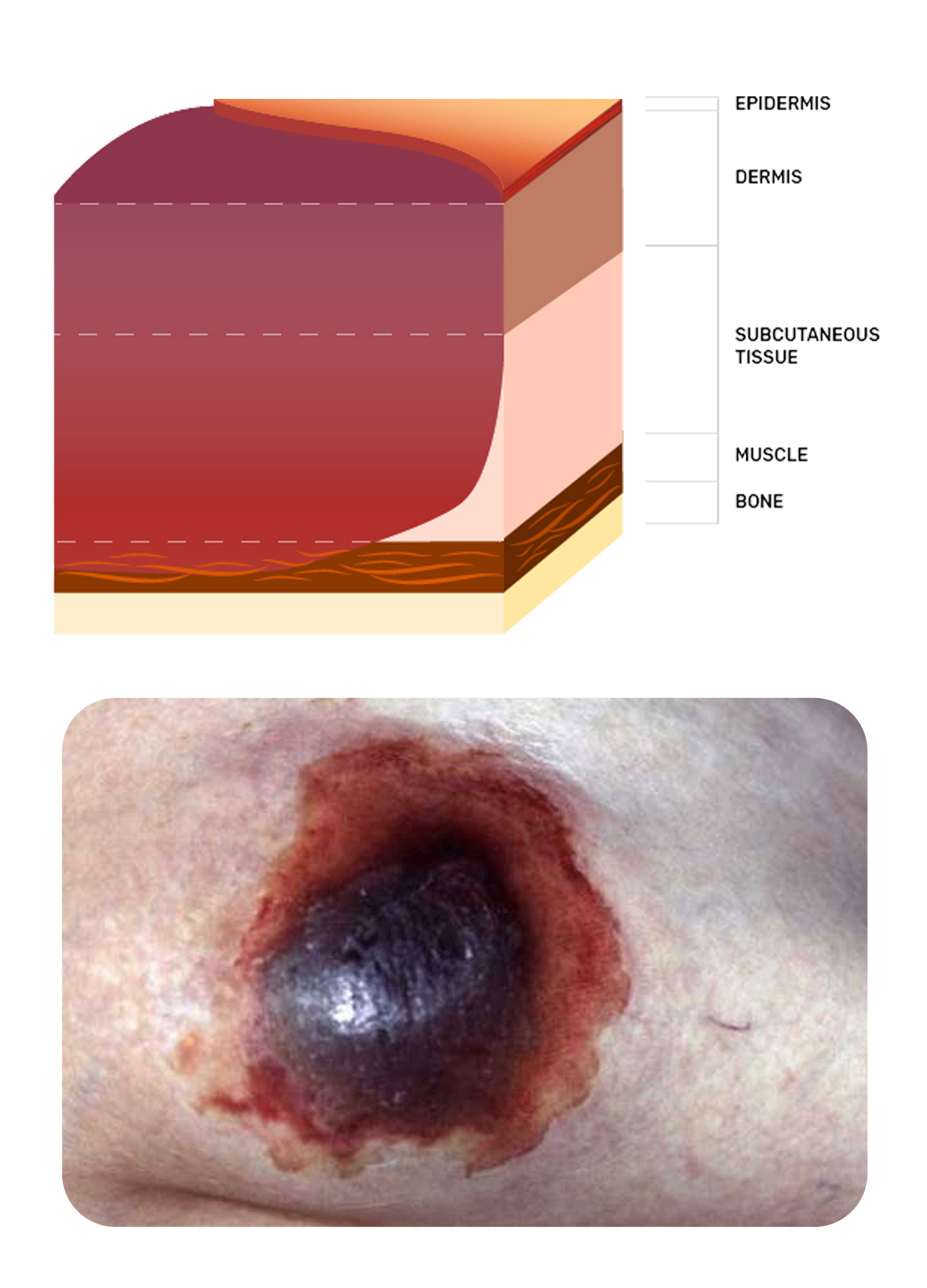

Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (Depth Unknown)

Suspected deep tissue injury (depth unknown): purple/maroon localised area of discolouration of intact skin or blood-filled blister. May develop a thin blister or eschar over a dark wound bed.

The aim here is to preserve the tissue intact for as long as possible and await what the body can do if the pressure is removed. Most clinicians take a watch-and-wait approach. Dressings that seal the area off can sometimes create more moisture and heat, making the tissue more vulnerable to further damage. Therefore, drying the area so that the dry blister skin can be removed later is the aim, provided pressure reduction/relief takes place. Povidone Iodine gauze pads may be used to achieve this drying effect as it is a 70% alcohol product.

Leg Ulceration

Although there are many types of leg ulcers, the most common are venous, followed by arterial, and then mixed venous arterial.

The classic signs and symptoms of each ulcer type can be found in the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers.

Ulceration of the lower legs is often complex as the diagnosis may not have been made. Without a correct diagnosis, patients often go from one practitioner to another. Therefore, it is paramount that work is done to establish a diagnosis.

Venous ulcers can heal with compression therapy, but conversely, some arterial ulcers may deteriorate if compression is used.

Therefore, having a knowledge of the characteristics of venous and arterial ulcers is imperative to ensure appropriate decision-making regarding the management of these wounds.

Venous Ulceration

Venous ulcers are located in the lower third of the lower leg and generally are superficial and weeping.

The priority of care is managing oedema and encouraging the epithelium to grow across the superficial break.

Zinc paste bandages and compression bandages are the mainstay of treatment to achieve these goals. The zinc paste bandages may include products like Viscopaste™ or Varicex™.

If the wound has been present for a considerable length of time, then some bacterial involvement is likely, so an antimicrobial such as Iodosorb Powder™, Inadine™ or Sorbact compress™ is suggested. This could then be combined with a super absorbent pad such as Zetuvit Plus™.

Compression therapy selection is complex and must be tailored to the patient. A safe and effective system from which to start, however, is the use of straight, elasticated tubular bandages, for example, Tubigrip™ or Tubular Form™.

These must be applied from the toes to the knee after selecting the appropriate size according to the manufacturer's guide. Commence with one layer; if tolerated, then add a second layer but extend to only two-thirds of the lower leg. Finally, if tolerance is maintained, then add another one-third. This is known as a three layers straight elasticated tubular bandage. Allow removal of the upper layers for sleeping, then re-apply the next morning.

More recently, it has been proven that surgery for vein issues does help to reduce the recurrence of the ulcer, and many GPs now have training in vein surgery - sclerotherapy.

Arterial Ulceration

When it comes to managing arterial ulceration, a vascular surgeon is best to consult, as, ideally, some surgery can be performed to restore perfusion to the limb. It then becomes the attending clinician’s role to prevent infection.

Generally, the rule is: if the tissue is dry and ischaemic, then keep it dry. Betadine™ lotion is used to achieve this and keep the eschar dry.

If the tissue in the arterial wound is offensive, infected or malodourous, then a silver or cadexomer iodine may be used, such as Aquacel Ag Extra Plus™ or Iodosorb™ ointment/powder.

Conclusion

Identifying the wound type, setting a clear aim for management and then selecting a product or device remains the mainstay of wound management. There are, of course, many other factors to be considered when addressing patients with wounds, and reviewing a wound in isolation from these other factors may lead to poor healing progress.

Nutrition, skin care, patient motivation, financial circumstances, environment and psychological state all play a part in wound healing. It is best to have a structure in assessment in order to decipher the wound aetiology, look at factors influencing healing, address these as able, and then select a product based on the aim.

Keep your formulary up to date with what is considered best practice, and review the wound regularly to ensure progress.

Topics

Further your knowledge

References

- Australian Wound Management Association & New Zealand Wound Care Society 2011, Australian and New Zealand Clinical Practice Guideline for Prevention and Management of Venous Leg Ulcers, Wounds Australia, viewed 12 December 2024, https://woundsaustralia.org/int/woundsaus/uploads/Publications/Standards%20and%20Guidelines/2011_awma_vlug.pdf

- Dowsett, C, Protz, K, Drouard-Segard, M & Harding, K 2015, Triangle of Wound Assessment Made Easy, Wounds International, viewed 12 December 2024, https://woundsinternational.com/made-easy/triangle-of-wound-assessment-made-easy/

- European Wound Management Association 2024, Resource Library, EWMA, viewed 23 December 2024, https://ewma.org/resource-library/

- International Wound Infection Institute 2022, Wound Infection in Clinical Practice: Principles of Best Practice, IWII, viewed 12 December 2024, https://woundsinternational.com/consensus-documents/wound-infection-in-clinical-practice-principles-of-best-practice/

- Leaper, DJ, Schultz, G, Carville, K, Fletcher, J, Swanson, T & Drake, R 2012, 'Extending the TIME Concept: What Have We Learned in the Past 10 Years?', International Wound Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1-19, 12 December 2024, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01097.x

- Lipsky, BA & Hoey, C 2009, 'Topical Antimicrobial Therapy for Treating Chronic Wounds', Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 1541-9, 12 December 2024, https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/49/10/1541/297363

- National Health and Medical Research Council 2021, Nutrient References Values: Australia and New Zealand, Australian Government, viewed 12 December 2024, https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/nutrient-reference-values

- Vowden, K & Vowden, P 2002, Wound Bed Preparation, World Wide Wounds, 12 December 2024, http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2002/april/Vowden/Wound-Bed-Preparation.html

- Wound Healing and Management Node Group 2013, 'Wound Management: Debridement - Autolytic', Wound Practice and Research, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 94-5, 12 December 2024, https://journals.cambridgemedia.com.au/application/files/1916/0506/1130/2102_10.pdf

- Wounds International 2024, Best Practice Statements, Wounds International, viewed 12 December 2024, https://woundsinternational.com/category/best-practice-statements/

New

New